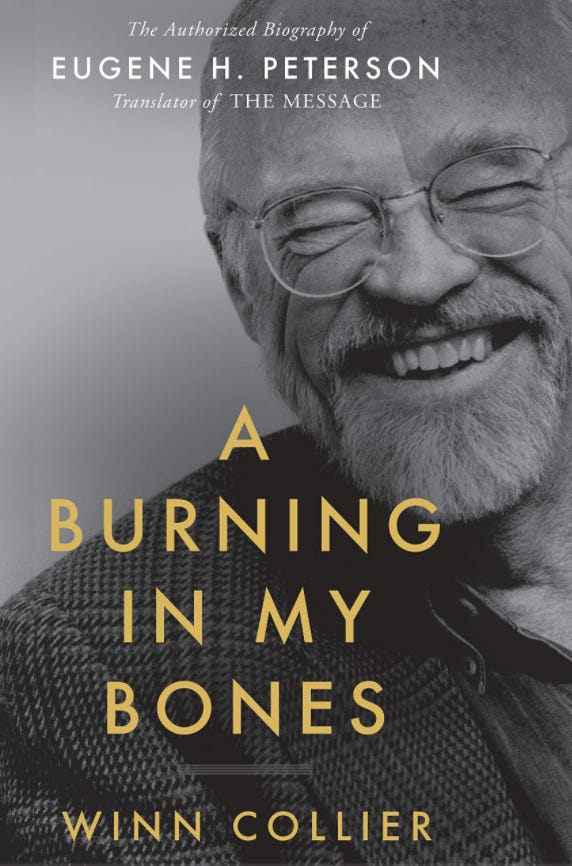

Some pastors see themselves as preachers, as teachers, as entrepreneurs, as leaders, as visionaries, or as equippers. Eugene Peterson, as we read in Winn Collier’s biography of Eugene Peterson called A Burning in My Bones (pp. 120-147; for the reading plan), saw himself – along with Jan his wife – as someone who pastored people. He saw the pastor as a spiritual director and as one who led his people to worship God and fellowship with one another.

Photo by Daan Stevens on Unsplash

How a pastor – actually anyone ministering to others in whatever capacity and with whatever giftedness – envisions herself matters immensely. We all work out of our self-perception and self-conception. Living out of how others perceive us or living up to their expectations leads to burn out. Self-awareness matters. Peterson lived from self-awareness. A kind of self-awareness that was conscious of not fitting lots of the stereotypes. He got along as a sometimes dissident.

He believed a pastor pastored out of a relationship with God, out of time with God. Many today are so busy doing things for God they have no time with God. The culture created by the busy-pastor demands more busy pastors. To shift from a busy-pastor to a with-God pastor will require discipline and patience and time to form into a new culture. Ponder these citations from Collier/Peterson and offer your thoughts in the comment box below.

What happens to church when pastors are like this?

What happens to ministry?

What happens to seminary classrooms?

Some of my favorite quotations in today’s reading:

“I think I’ve always been a pastor – but I just didn’t know what a pastor was.”

A life-long gripe by Peterson was the business model or the manager model.

“The ink on my ordination papers wasn’t even dry before I was being told by experts, so-called, in the field of church that my main task was to run a church after the manner of my brother and sister Christians who run service stations, grocery stores, corporations, banks, hospitals, and financial services.”

“Eugene felt alarmed. Not only because he sensed in his gut that this approach decentered God, but because so many of these perceived needs were actually destructive, dehumanizing. Even antithetical to the gospel of Jesus.”

What kind of pastor did he want to be? That’s the focus of these two chapters.

“The community did not need a church to craft little programs to assuage their consciences or perceived needs for safety. It needed the church to invite people into a new reality ruled by the kingdom of God. Christ Our King [his church’s name] needed to worship.”

So he refocused:

“Instead, they began to focus on who they were. There in the little cinder block catacombs, with just fifty or sixty people gathering weekly, they could learn one another’s stories. They could gradually find themselves caught up together in what God was doing in their corner of the world. … For any of this to be real, Eugene knew he had to get to know the people and their children and their stories. …

Every week, he wrote three names on a three-by-five-inch card and propped it on his desk. He kept those people in his sights as he prayed and studied that week’s text. It was all very primal.”

Good word there: primal.

The busy-pastor thinks she’s doing the work.

“Eugene was hung between two competing visions of what it meant to be a pastor. Preaching from Acts, he saw how clearly everything depended on God. But tossing in bed late at night or poring over endless financial forms whose figures made dark prophecies, it felt as though everything depended on hirn. And he was not sure he was up for the job.”

One of the temptations for pastors today is to wander into becoming a therapist and a counselor and psychologist. He was there when this became the fashion:

“For two years, Eugene acquired tools to better understand trauma and enter the pain of those he pastored. Exhilarating for him, he learned unambiguous solutions for dealing with pastoral ambiguities, ways to motivate people and give them clear direction for their struggles. … He began to notice “a latent messianic complex,” where he was drawn to locate the emotional problems among those in his congregation and then fix them, efficiently. These experiences taught Eugene to value psychiatry and therapy (an appreciation he never lost) … but he did have to wrestle, coming to the realization that he was a pastor, not a therapist. [Instead, he realized] “I was … calling them to worship. Worship was the call. Worship was the work” (132).

What kind of pastor would he be? A contemplative, with-God kind:

“Those mountains are magnificent,” a pastor friend told him, but they have twenty different ways to kill you. Just like the church.”

He responded: “Eugene couldn’t shake that line. Weeks later, he called Wilson and explained his vague sense of the kind of pastor he wanted to be: slow, personal, attuned to God and to the lives of those in his parish. Eugene wondered if it was possible to transform from a competitive pastor to a contemplative pastor – “a pastor who was able to be with people without having an agenda for them, a pas-tor who was able to accept people just as they were and guide them gently and patiently into a mature life in Christ but not get in the way.”

So much to think about in these two chapters.

These are all wonderful comments and I'm just watching and reading and basking in this conversation. Thanks to each of you.

My favorite quotation from this week’s reading:

Some assume Eugene had an inbred revulsion for the modern addictions to success and winning, as though his loathing for these driven impulses were simply part of his DNA. Quite the contrary. Eugene was so attuned to the temptations because they were such deep struggles in his own soul.