“What,” the American church history professors, asks her class, “are some turning point events/moments in American church history?” The American historian is

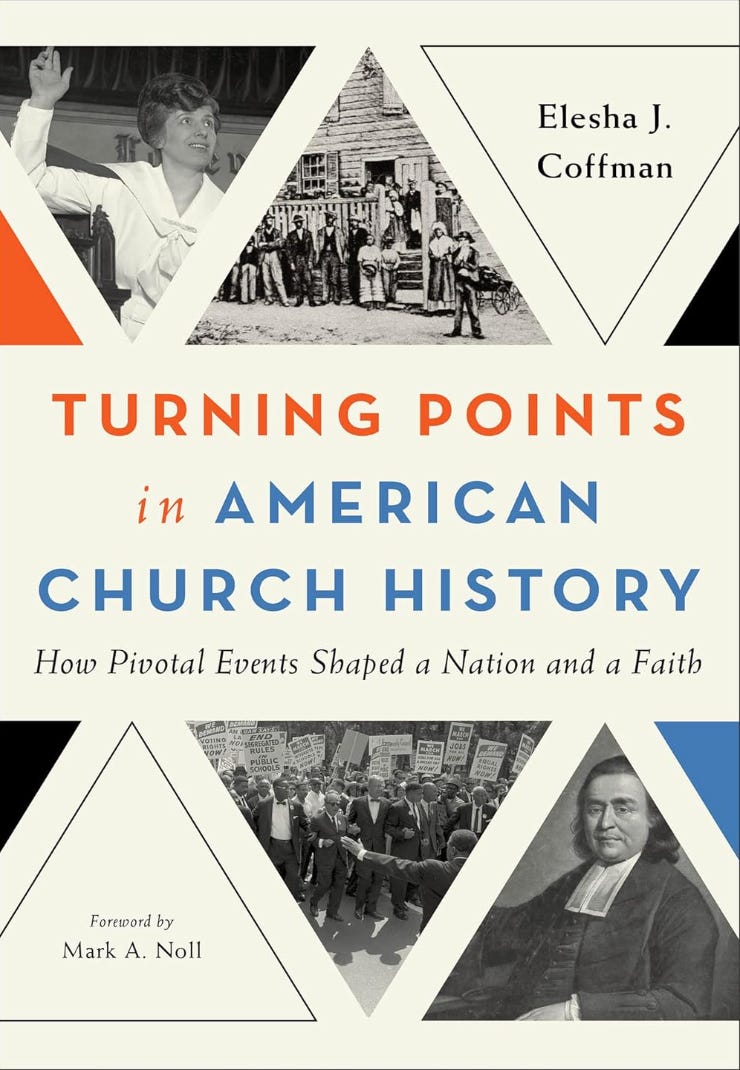

Elesha Coffman, and she asks asks that question to herself and answers it in her new book, Turning Points in American Church History: How Pivotal Events Shaped a Nation and a Faith (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2024).

Event #1: The defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588.

Which raises the question of how an event over in the English Channel could impact what did not yet even exist as we know it today – the colonies that became the USA. All I can say is that I found the chapter both informative and interesting.

Beginning with the oddities of Spain’s King Philip II, a champion of Catholic Christendom, hauling a flotilla of ships from Spain into the English Channel on its way to conquer the burgeoning power of England. By “Spain” is meant as well the various areas now called Portugal, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and much of Italy. The ships were adorned with the Crusader flag since the battle was God’s, and it was a battle to regain the nations and allegiance, along with money and power, of those who had rebelled against Rome and taken up residence in the world of the Protestants. As a turning point, the Armada represents Catholic European Christendom and England’s navy, led by Lord Admiral Charles Howard and Francis Drake, represented freedom from the Pope and the integrity of the Protestants, not to ignore the freedom of the seas, trade, resources, and power. “Money, power, and the ascendants of ‘true’ religion were incredibly potent motives on all sides.” The battle was between 130 ships for Spain and some 200 for England.

Who won? The wind and the weather. How was that explained? God. Medals were struck that said “God blew, and they [the Spanish] were scattered.” It was common then, and is for some to this day, to think of God as the one who controls the victors in war. “Participants on all sides took for granted that God had directed the outcome for his own purposes.” Since these were Christians of one sort or another, both sides had inherited the Deuteronomic theory of history so evident in Israel’s scriptures. When village after village and Puritan after pilgrim were destroyed in King Philip’s war, Boston preacher Increase Mather asked, “Why should we suppose that God is not offended with us, when his displeasure is written, in such visible and bloody Characters?” Puritan theology could explain it in no other way.

The battle was won, too, on the sea. Howard “launched a night time attack of fireships – 8 unmanned boats, set ablaze, guns loaded, were towed toward the Spanish and then unleashed on the tide.” The result was the scattering of the fleet, and their route home was counterclockwise around the English isle. During that trip many of the Spanish fleet died. “Dozens of ships wrecked off the coast of Scotland and western Ireland … many sailors who survived the wrecks were slaughtered on shore… [and] that nation lost perhaps as many as half of its sailors by the end of the year too, mostly killed by disease.”

“God favored Protestants and would aid them in the future. This claim was the most important legacy of the defeat of the Armada. With a rising power, England, in the Protestant camp, the dream of a reunified Catholic Christendom failed, and imperial control of the new world became an open, and very hotly contested, question.” The defeat gave England the imagination of colonialization, which became the USA.

Of course, as a Bible guy who daily notices this theory of providential history, the explanatory power of the a divinely orchestrated war lands both naturally and with buckets of doubt about God’s involvement in these wars. Winners claim God; losers may take it as discipline.

Coffman uses this story to open the window on the age of Spanish ships and colonialists from Europe into New Spain (modern North and South America), with the Portuguese, French, Dutch, and English taking up locations (and resources and lives as well). Europe’s diseases wiped out Indigenous populations, which is one of the greatest tragedies of the era. Robert Chao Romero, in Brown Church, had many other stories to tell of this period, though Coffman’s story does not tell those stories. On the lands of “New Spain” these various nations competed for people, for territories, and for resources. The ostensible motive of conversion, articulated by none other than one Christopher Columbus, was haphazardly enacted.

The names of places – St Augustine to New Amsterdam/New York to Quebec tell the stories of the colonialists.

Thank you Scott.