The Eastern Orthodox Church has a major emphasis on Good Friday through Easter and the emphasis is on what is sometimes called the "harrowing of hell," the descent of Christ into hell between the Cross and the Resurrection. The idea is that Christ entered into Hades after his death and raided hell to ransom the righteous of the Old Testament.

This is the classical theology of Holy Saturday.

Clearly, then, the death prior to Christ's death was not final. Is the death after the death of Christ final, then?

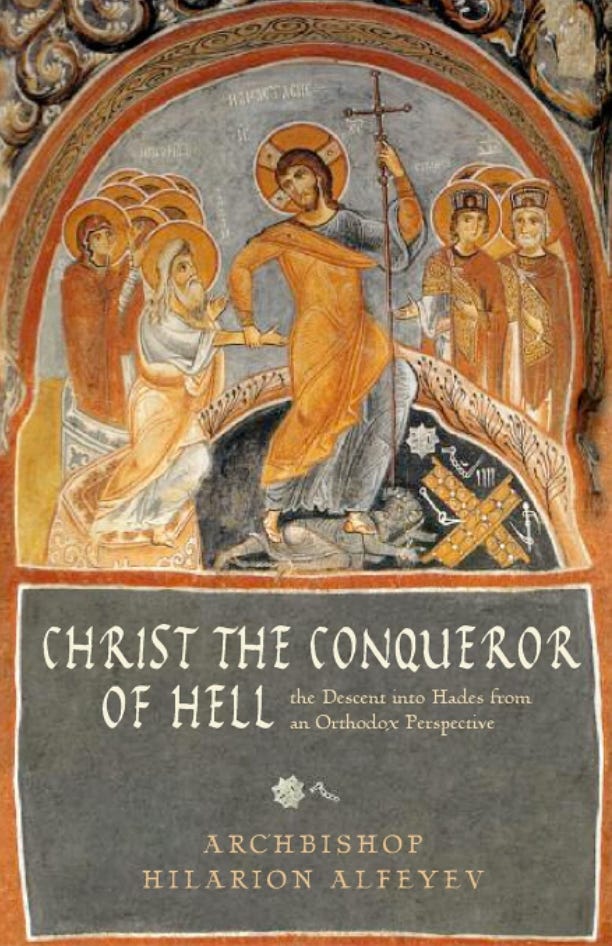

I read the pious and and learned study of Archbishop Hilarion Alfeyev (Christ the Conqueror of Hell: The Descent into Hades from an Orthodox Perspective), mostly because I've always wanted to read a good piece by an Orthodox theologian on the Eastern (and traditional) sense of the "descent into Hades," an article in our creed. There are a number of NT texts that, while open to dispute, have been traditionally understood as referring to Christ's descent into hades and they are, if so, clear signs that one kind of death was not final.

Matthew 12:40: For just as Jonah was in the belly of the huge fishfor three days and three nights, so the Son of Man will be in the heart of the earth for three days and three nights.

Matthew 27:51-52 Just then the temple curtain was torn in two, from top to bottom. The earth shook and the rocks were split apart. And tombs were opened, and the bodies of many saints who had died were raised. (They came out of the tombs after his resurrection and went into the holy city and appeared to many people.)

Acts 2:31: David by foreseeing this spoke about the resurrection of the Christ, that he was neither abandoned to Hades, nor did his body experiencedecay.

1 Peter 3:18-21: Because Christ also suffered once for sins, the just for the unjust, to bring you to God, by being put to death in the flesh but by being made alive in the spirit. In it he went and preached to the spirits in prison, after they were disobedient long ago when God patiently waited in the days of Noah as an ark was being constructed. In the ark a few, that is eight souls, were delivered through water. And this prefigured baptism, which now saves you - not the washing off of physical dirt but the pledge of a good conscience to God - through the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who went into heaven and is at the right hand of God with angels and authorities and powers subject to him.

1 Peter 4:6: Now it was for this very purpose that the gospel was preached to those who are [now] dead, so that though they were judged in the flesh by human standards they may live spiritually by God's standards.

Eph 4:9: Now what is the meaning of "he ascended," except that he also descended to the lower regions [of] the earth?

Rev 20:14: Then Death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. This is the second death - the lake of fire.

The New Testament evidence, when read in its context, almost certainly indicates that Jesus "did" something between the Cross and the Ascension. The texts cited already, in particular 1 Peter 3:18-25 and Acts 2, as well as the baptism for the dead in 1 Cor 15 and that enigmatic text in 1 Peter 4, indicate to me that we should be open to Jesus either gospeling the dead or announcing the good news to the dead after his death and before his ascension.

Do these texts indicate that death is final? One of the comments elucidated what I mean by "is death final?" when it suggested that the first death is not final but the second death is final.

The question the Church has asked, and some are surprised by this, is whether that second death is final?

Does it matter to your way of doing theology that the early theologians all believed in a descent into hades?

Here's a basic historical conclusion, and it is sketched in readable detail in Alfeyev's book: into the 4th Century, Christians in both the West and the East clearly affirmed the descent into hell, the victory of Jesus over death, and either the liberation of saints from the realm of the dead or the total liberation of all humans from the power of death and hell.

Here are some details:

Irenaeus is typical in seeing both the descent and a release of the patriarchs, prophets and saints from the Old Testament period.

Hippolytus: John the Baptist also descended to preach to those in hades.

Clement of Alexandria: Christ descended and preached to the saints and to the Gentiles who lived outside the true faith. Hell for him was a place of reformation. Origen is like Clement, but emphasizes human choice.

Issue: how to define the various terms, but many saw places. That is, there's Abraham's bosom, and hell, and hades, and a prison.

Athanasius: leans, at times, toward the universal redemption or release from death. The famous text "Christus patiens," attributed by some to Gregory Nazianzen, poetically sketches a universal release of the dead through the descent. Cyril of Alexandria follows this line of thinking; so does Maximus the Confessor.

Many are somewhat ambivalent or clearly believe Jesus' release was only for the saints, and an example is St John Chrysostom. John Damascene emphasizes human choice by those in the realm of the dead and so not all are liberated. St Jerome is in this camp of saying at times that all are liberated but other times not all are liberated.

A decisive voice in this issue, especially in the West, was Augustine who believed in both a descent but not all in a "second chance". For Augustine, death was final and the only ones in hades who were released were those who were predestined in God's elective grace. What is interesting, though, is that Augustine was clearly battling many who did think Christ emptied hades and death and hell of all its inhabitants. Gregory the Great completed the Augustinian perspective.

Alfayev emphasizes that the Eastern fathers did not spell things out the way the Western fathers did.

Dante took theology about the afterlife and turned it into an epic adventure, modeling his story on Homer's stories and on Virgil's famous The Aeneid and in many ways taking them to the next millennia of history.

In the East, instead of finding a Dante's journey into the underworld and then back up to heaven, we find poets who told stories of Christ's victory of Death and the Devil and Hell. The principle poets are Ephrem the Syrian and Romanos the Melodist. Their poetry, which has been said to be some of the best in the world, puts into words the theology of what Christ accomplished between his death and his resurrection/ascension.

Do you believe in the descent into hades (after the death of Jesus)? Why or why not? What part does this theology of the fathers play in your understanding of the descent?

As I dipped into the Eastern theology poems by reading Alfayev, what struck me was how personified and mythic and epic everything had become. Here are the principle themes:

Christ, the protagonist, breaks the gates and bars of Hades, overpowers Satan and his ministers, and breaks their resistance. Christ then illumines Sheol with is light, destroys Death and opens the way for the dead to rise. What we see in the poetry of the East is a near universal, if not universal, victory over death and hades and hell and Satan. Which borders on a kind of universalism.

Alfayev sums up his study by noting four views of the effect of Christ's descent:

1. All are liberated from hell and death (Orthodox liturgical emphasis).

2. The OT saints are liberated (Eastern patristic tradition emphasis; West after Augustine).

3. Those who followed Christ [elect] were liberated (Augustine).

4. Those who lived by faith and in piety were liberated (West; after Augustine).

Alfayev sees Scripture as prominent in authority with the liturgical texts second. The councils, which are specific responses to specific issues at specific times, are alongside the liturgical texts. Then the fathers opinions.

Thus, the descent for Alfayev is doctrine but how many find salvation is private opinion. The most pervasive view, as I read him, is that only those who believe are saved.

This subject has been on my mind all week. For many years I realize I was influenced by either church history (my own as well as that of the saints), Milton's writings, and sermons I'd heard over the years. This year I decided to do a deep dive myself. The I Peter 3:19-20 passage; Matthew 27:50. I poured over this writing for today twice. Primarily I rejoice that He paid the price and that His mercy runs deep.

Scott, your deep dive into the liberation of the Saints in Hell from an Orthodox perspective is truly enlightening. As someone who has been exploring the Anglican/Orthodox traditions after being rooted in a more Evangelical culture, I find myself increasingly drawn to the richness of theological, liturgical, and scriptural nuances that may have been overlooked before. This concept of Christ's liberation of the Saints between the Cross/Resurrection events carries significant implications for my understanding of salvation in the nature of Christ's redemptive work. You said it yourself, in the Orthodox tradition, this event is referred to as the "harrowing of hell", emphasizing Christ's triumph over death in the grave. It is profound and shouldn't be underestimated. For me, it carries implications for the deeper understanding of Salvation and the assurance it offers to Christ followers...it speaks of the comprehensive nature of Christ's redemptive work extending beyond the boundaries of time and space. It reminds me that the same power that raised Christ from the dead is at work within us, enabling us to live victoriously in the midst of life's challenges. It invites me to trust in Christ's promises... to live with renewed sense of hope and assurance knowing that nothing can separate us from the love of God in Christ our Lord. While I explore these deeper theological dimensions, it not only enriches my spiritual journey but also opens up new perspectives on the unity of the church across different traditions. It reminds me of the importance of delving into the Theological AND historical foundations of our faith, allowing me to appreciate the diverse interconnection of Christian thought and practice. Thank you for sharing your insights and prompting for the reflection of these essential aspects of our faith journey. Appreciatively and Happy Easter to you and yours.