Deconstruction and Dystopia

In her 2017 essay “No, We Cannot,” the historian-essayist Jill Lepore connects dystopias like Gulliver’s Travels or The Handmaid’s Tale to utopias. That is, dystopias are apocalyptic-type reactions to the mapping of utopias. Think then of George Orwell’s novels responding to fascism, communism, and socialism.

By the way, “utopia” means “no place” while “eutopia” would mean the “good place,” and most utopias today are far closer to eutopias than utopias. Fair enough? OK. On we go. You can find Jill Lepore’s essay in her wonderful new book, The Deadline: Essays. Here are some of her macro-statements about utopias and dystopias:

A utopia is a paradise, a dystopia a paradise lost.

The latest blighted crop of dystopian novels is pessimistic about technology, about the economy, about politics, and about the planet, making it a more abundant harvest of unhappiness than most other heydays of downheartedness.

A utopia is a planned society; planned societies are often disastrous; that's why utopias contain their own dystopias.

Dystopia unism turns out to have a natural affinity with American adolescence. [Thinks Lord of the Flies.] As in, “I grew up a little, and I gradually began to figure out that pretty much everyone had been lying to me about pretty much everything.” So a high schooler.

Every dystopia is a history of the future.

The current fad for dystopias, she observes, is a “duel of dystopias … a proxy war of imaginary worlds.”

As I read Lepore’s essay I began to ponder the rise of deconstruction among evangelicals leading to a pervasive post evangelicalism in the USA. I believe deconstruction today is the dystopia to the previous generations utopia of what they believed could occur through evangelicalism’s potential impact on society and the world.

I wonder what “utopia” you heard or embraced in your former days?

Here are some utopian figures, heroes, and themes that I have witnessed in my life and you may have noticed in the previous generation. Think of Dallas Willard and Richard Foster’s hopes for spiritual renewal and formation among evangelicals.

Or, think of Brian McLaren and Rob Bell’s impactful challenges to evangelicalism and mapping of a different future, a future that would be far greater. Both of these figures at times were connected by critics to post millennialism, which is a utopian vision of Christian eschatology.

And I also think the mega church vision for the American evangelical church as articulated by Bill Hybels, Andy Stanley, and Rick Warren carried with it utopian visions of what the evangelical church could be.

Now map on top of that, in the wake of Ronald Reagan, the pervasive hope and vision of so many evangelicals when it came to impacting the American government. The rise of the homeschooling movement, the interest in politics, young evangelical (mostly) men entering into the world of law and politics, and the vision that evangelicals could exercise significant impact on elections. This too had a utopian worldview at work.

So, whether it was a mega church vision, the impact of new pragmatics, small successes in political influence, theological optimism, charismatic salesmanship, missional resolutions, or a Neo-Anabaptist witness – all these smack at times of utopianism or eutopianism.

Deconstruction clearly met these figures, heroes, and themes with the dark clouds of dystopia. Deconstruction points the same audiences to the pervasive and stunning failures of leading pastors. They are unafraid to describe revelations of malformed character among evangelical leaders. Deconstructionists know the #MeToo movement, the sordid revelations of powerful men who silenced, suppressed, oppressed, and violated women and men. They have their eyes on megachurch pastors, the Southern Baptists, and Roman Catholics. They have a radar out that says power corrupts. They are not surprised by Mark Driscoll’s antics. And there is a pervasive criticism of evangelicalism’s political capitulation to the Republican Party among deconstructionists.

Deconstructionists are asking questions in their dystopias about what the Bible says, what it means, and how we are to make use of passages in the Bible that challenge many of us. Deconstructionists are finding seal logical answers in previously rejected theologians. They have turned their back on the boilerplate systematic theologies and authority figures that previously exercised significant influence in their circles. They are unafraid to express their doubts, not only on social media, but also behind the pulpit on Sunday mornings. They are asking questions about sexuality and sexual orientations.

Evangelicalism’s utopias and eutopias have met their match in the next generation’s dystopian deconstructions.

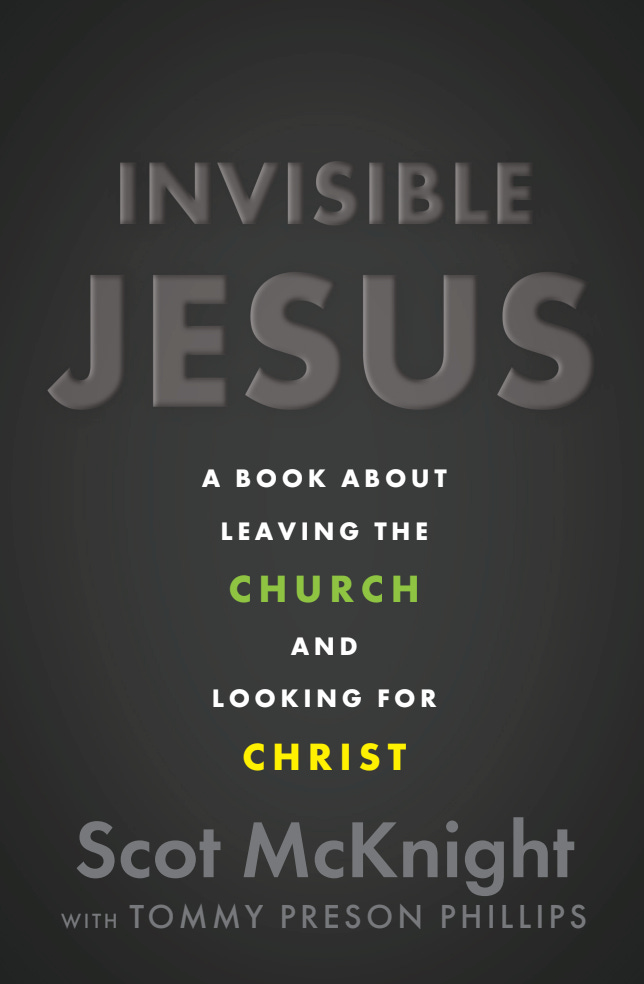

And very frequently they go to church and they discover that Jesus is invisible. This Substack anticipates some themes you will find in a book I wrote with Tommy Phillips called Invisible Jesus, scheduled to appear this autumn.

Here’s what the cover could look like:

I look forward to reading the book! And - I like the cover :)

In line with these examples, is A Church Called Tov (which I loved and shared with others) a utopian project? And regardless, how do we avoid slipping into Utopianism? It seems pervasive.