How Should We Christians Talk about God?

Valerie Hobbs, a specialist in theo-linguistics, gives us five suggestions

How should we as preachers and teachers talk about God or use God-talk?

How should we as Christians use God-talk in public?

What’s your wisdom to the above?

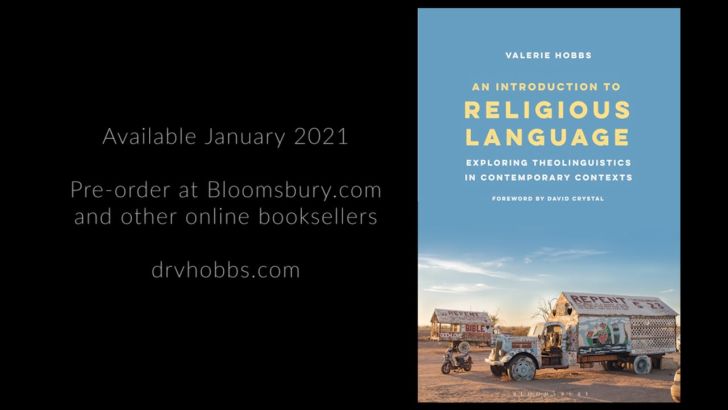

I asked Valerie, who is the author a wonderful new book about how religious language works and what it does, if she could give us some suggestions for how to use religious language. I’m so honored she has offered the post below:

Dr. Valerie Hobbs

Senior Lecturer in Applied Linguistics

School of English

University of Sheffield

Author: An Introduction to Religious Language: Exploring Theolinguistics in Contemporary Contexts (2021)

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/an-introduction-to-religious-language-9781350095755/

Watch a video abstract here:

Find me on the web: https://drvhobbs.com/

Or on my university profile: http://www.shef.ac.uk/english/people/hobbs

1. Religious language is some of the most powerful language in our linguistic repertoire. We use it to articulate and affirm our deepest held commitments, to draw close to the unknown, to God and to His Creation. Through it we build community and cope existentially at times of loss, joy, wonder and fear. But religious language is a two-edged sword. It is the language of blessing and also the language of violence. We may summon its power in protection of others, to build and guard community boundaries from religious criminals who threaten a community’s core beliefs and its people. Likewise, religious language is the language of abuse and of manipulation. It is one means by which we accumulate and retain power, by which we curse and destroy others.

2. Religious language is of course common in overtly religious contexts. But it also tends to appear at moments when a community’s or an individual’s deepest held beliefs are called into question. What does it mean to be human? What is right and wrong? Where did we come from and where are we going? Who is God and what is He like? This is why we often find religious language during periods of conflict and crisis, involving high stakes, and at periods of key life transition like birth, death, marriage, at moments where our identity shifts in some way.

3. Everyone uses religious language, whether they affiliate with organised religion or not. The religious language that people use often comes from the world religion that they are most familiar with. This can include explicitly religious vocabulary, religious metaphor and quotes from sacred texts, among other things. But religious language is any language we use to do religion, that is, to make sacred the world and, on the flip side, to determine what and who is taboo or profane. Any language we use to distance or exclude someone from a community united around a set of fundamental beliefs, no matter how subtle, constitutes a religious act, for example.

4. Religious language, like all language, is not just individually but communally constructed. How does this happen? Part of this is simply because language involves communicating and negotiating meaning with others. We need to talk and write in ways that others will recognise and be able to respond to. But also, privileged users of language in a religious community, people with recognised authority, hold particular influence over our language choices and the ways in which particular topics are talked about and particular texts are structured. Consider the influence that prominent theologians and other religious leaders have had on how we talk and think about certain passages of the Bible. Or consider the religious language which appears on the world’s stages, in politics, in advertising, in news media. Throughout history, many have wielded religious language to convince us to buy a particular product, to vote for a particular politician, to eat a certain kind of food, to idolise a particular celebrity, to cheer for a certain athlete, to live in a certain way, to place our identity, our hope in this or that person or thing.

5. The power, potential and pervasiveness of religious language means it’s vital that we reflect on our language choices and the language choices we encounter. We must consider carefully what ideas about God, about other human beings and about the world we so often unconsciously absorb and perpetuate through language. Where we have learned to speak in ways that contradict the Gospel by which we have been saved, our religious language must be a language of resistance. A language of love and peace.

There is a lot of religious language (and godtalk) that bothers me. I so tire of people saying: “God has so blessed me because mine was the only house left standing in a massive ice storm or fast-moving fire.” Or ‘We are so blessed to be able to buy this lake home right after the multi-million-dollar price went down.” Or, “It was a miracle that my cab blew a tire; I missed my flight---the one that crashed leaving 192 dead.” I personally would be terribly relived to realize that the delayed cab saved my life, but I struggle with all the blessings from God and the miracle stories like that.

I wonder if this also relates to survivors’ guilt, and perhaps also a complete lack of practice in the language of lament in our churches.