On "Evangelical," Who Decides?

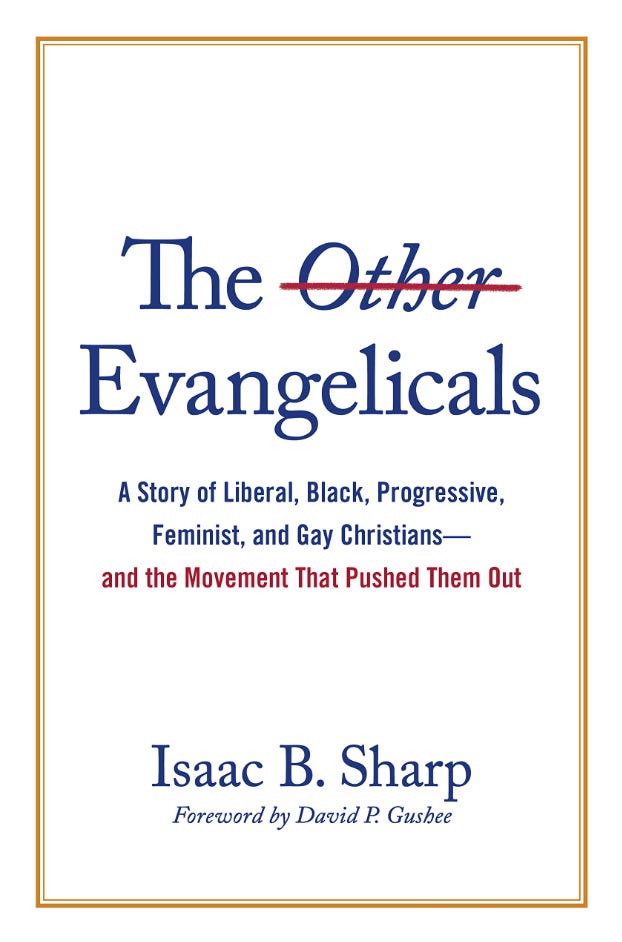

The argument of Isaac B. Sharp’s The Other Evangelicals is that the gatekeepers of evangelicalism have decided who’s in and who’s out.

It’s a good question, isn’t it? Who decides who’s one and who’s not. Take a look at this way. Some people say they are evangelical so they are. I remember listening to Phyllis Tickle, in a dingy conference center in San Diego say she was an evangelical. I chuckled. No way, I thought. But if she says she is? Others say one must belong to an official evangelical church or denomination, which puts the power in the hands of the denomination’s or church’s doctrinal statement. So, someone says she goes to an Evangelical Covenant church so she’s evangelical. Plenty in that denomination would not say they are evangelical, at least in the way the term is used almost everywhere in the USA today.

Others compose a list of constant beliefs of evangelicals, which looks like Bebbington’s famous quadrilateral, which became famous in part because it was objective: Biblicist, Conversionist, Crucicentric, and Activist (evangelism, activism in society). Those categories have worked for a couple decades effectively. But some scholars have modified Bebbington, and it is a pity that John Stackhouse’s little book, Evangelicalism: A Very Short Introduction was not available to Sharp. Or, if it was, he chose not to interact with it. Stackhouse’s approach looks like this:

Six features make up evangelicalism for Stackhouse:

(1) Trinitarian;

(2) Biblicist;

(3) Conversionist;

(4) Missional;

(5) Populist;

and (6) Pragmatism.

Stackhouse’s six-point summary works for me as a good way of delineating who’s in and who’s out when it comes to the “evangelical” movement and culture, that is, if someone cares. Bebbington’s work suffices often for the major core beliefs and some of its behaviors.

But Isaac Sharp points to something that has most often been ignored. He contends in the 20th Century the self-appointed and inner-group-anointed gatekeepers rendered either implicit to explicit decisions on what fit their understanding of evangelicalism. Here’s how Sharp puts it:

In the process, evangelicalism mostly fundamentalistic, theologically and politically conservative, white, straight, and male-headship-affirming claimants successfully formed twentieth-century evangelical identity in their own image. By the dawn of the twenty-first-century, this is what US American evangelicalism looked like. This version arguably now represents what it means to be an official capital evangelical.

Sharp demonstrates, at least to me, that the questionnaires tend to ask what political leaning an evangelical has and then defines evangelical by their political leaning. There’s got to be, I said to myself over and over reading this book, something that defines evangelical more accurately than questionnaires based on self-identifying as an evangelical and then polling what such persons believe. It helps to do this.

Until it doesn’t.

True enough, the gatekeeper pushed some people off the platform, but was this more than a power play? I would say so. Sometimes it was because the major leaders, who often had the temperature of the evangelical churchgoers (remember, Stackhouse won’t let go of the populist nature of evangelicalism, which means the gatekeepers aren’t totally in charge), rendered decisions on the basis of both Bible and tradition. It wasn’t just some white guys in Wheaton’s CT conference room rendering a decision.

But it was at times.

Sharp describes that 2018 meeting of evangelicals at Wheaton who, at least to many observers, were there to declare evangelical doesn’t mean pro Trump – but the meeting fell apart without a statement. That reveals the essential issue at work. There are no authorities finally able to speak to such an issue that is clear to many (evangelical support of Trump was embarrassing) when that issue doesn’t square with the populist nature of evangelicalism.

The tension, then, at work in Sharp’s book over the gatekeepers may need another explanation, namely, the leaders are not without their populace. They can speak for them and even turn them sycophantic at times. But they can only lead so far and when the get to the edge, the populists cry foul and that leader loses his status. Evangelicalism then is a congregants’ movement on whose shoulders the gatekeepers stand, as long as they repeat what that mass of congregants like.

Maybe the gatekeepers render decisions in order to maintain their status.

Yes, there’s a core theology (Bebbington) and a fair-minded way of describing the movement (Stackhouse) and there are leaders calling the shots that are more or less safe (Sharp), but one can never exclude the millions of folks in the pews whose instincts cannot be offended too much.

So from what I am hearing, that old saying seems to be true; "There go my people, I must lead them." The tail is wagging the dog. And again, Evangelicalism is a "self defining" entity; anyone can declare they are one and anyone can declare their brand the peoples choice at any given moment? No wonder I didn't fit the mold and was so frustrated?

This post is helpful, but as I read it, I put myself back into the 1980s as an informed woman in a fundamentalist pew. What mattered for me and thousands of other women was not any finetuning of a doctrinal statement, but whether or not we would ever have a voice that men would listen to. I suspect that even now - in spite of all the advances women have made in evangelical circles, it's still the guys trying to define something that for many of us increasingly feels irrelevant.