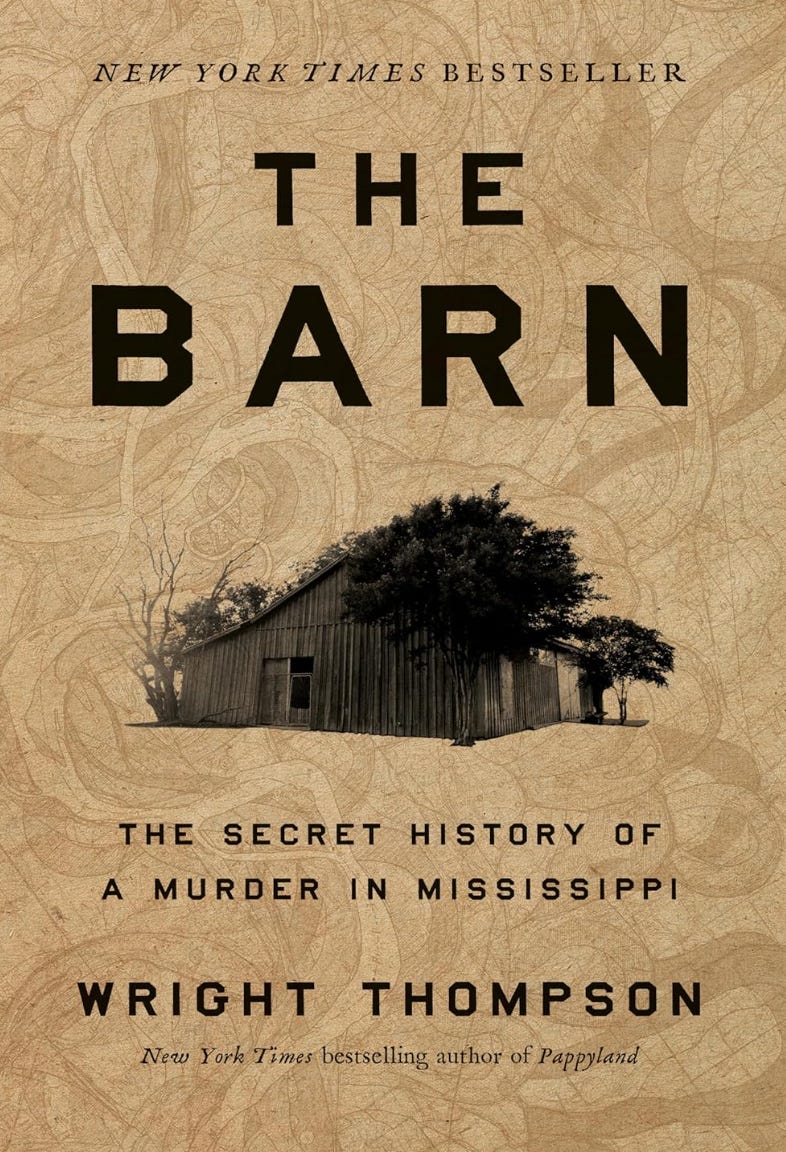

The Barn

A Mournful Sense of Inevitability

I must have turned back to the maps following the Table of Contents 500 times as I read the book. The connections of names, families, and generations that followed the maps, however, were too complicated even for the excellent family trees outlined by Wright Thompson in his stunning new book, The Barn. The subtitle reveals the story he mines, hunts, investigates, and reveals: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi. The Barn is not a page-turner; rather, it’s a book one cannot put down because one is sucked into the vortex of an evil that will not let go until the truth is exposed. I don’t want to read it again; I want to read it again.

A native of Mississippi’s Delta, Thompson wants the American public to know not only what actually happened to Emmett Till (he was brutally lynched) but also who was involved (the Milam-Bryant family tree names some of them), and how that story came to be untold, silenced, and nearly forgotten. By something on the order of 90% of those who live in the Delta and in Mississippi.

Words came to mind when, and still come after reading The Barn, words like “evil embodied” and “systemic evil” and “white supremacy,” but no expressions can tell this story. It must be told, detail by detail, name by name, and complicity after complicity.

We live in the suburbs of Chicago. We knew of Emmett Till, a young, thirteen year old Black man who, visiting family in the Mississippi Delta, was kidnapped at night from his bedroom, loaded onto a truck, and shuttled to a barn west of Drew, Mississippi, where he was murdered. Allegations against at least some of the perpetrators led to charges, which led to a rigged trial, and the accused were excused and set free to live lives mostly of misery and guilt. Emmett’s body, due to the persistence of his mother and an advocate or two in the Delta, was returned, the casket was opened, and all who cared to see saw the brutality of what happened. The story of Emmett Till can be for the current generation what Uncle Tom’s Cabin was for a century and half ago. The latter is a novel; the former is history uncovered.

The conspiracy to silence the story, with local government and education systems complicit in the conspiracy, meant local folks like Archie Manning, the original quarterback of a family of quarterbacks, had never heard of Emmett Till, his story, or the Barn. The murder occurred 3.1 miles from his home. One way to prevent light from shining on dark places is to cut off the electricity. Mississippi did and has done just that. Jason Stanley’s new book, Erasing History, makes for one good companion read to Thompson’s The Barn. Tyrants and fascists know that when a story is not told, the truth will not be known. But Wright Thompson, who is in no way the only person telling the story of Emmett Till, would not let the current complicities continue without someone establishing a new line of power to the light.

Words and institutions factor in: cotton, sharecropping, racism, guns and murder and corrupt courts and judges and rigged trials, along with systemics and profound levels of apathy and turnings-of-a-blind-eye to what could be seen should one want to see it.

Everything was in place at the same time, which is why I swiped words from Thompson’s book for the subtitle to this Substack’s post: “a mournful sense of inevitability appear” when one begins to comprehend the factors and actors involved in this hideous expression of broken human beings. Pages later he paints the same idea into words: “rarely has a more cowardly collection of humans been put in the exact right place at the exact right time to do maximum damage. Even at the last minute, Mississippi held the power to pull back from the brink. Instead its leaders pressed for more speed on a suicidal glory charge.” It was April Fool’s Day. The decision was in. Racism would be encoded in Mississippi’s public education. Brown v. Board may have become law, but it would not be so in Mississippi. In February the state demanded “universal conformity to the doctrine of segregation.” It became a crime for a white student to attend a school with a Black student. Voter registration laws were intensified. One law demanded that voters had to interpret a section of the state constitution. Records did not need to be kept. The state passed a bill to spend $88 million to make Black schools separate but equal. The money was not available and equal was shattered by separate. “Rarely has a more cowardly collection of humans” is right.

Thompson’s family was complicit. He writes, “as the descendant of liberals and conservatives, of owners of enslaved people and civil rights crusaders, I usually find it slimy to judge them from the moral safety of the future. It's trendy for southern writers to find a straw man ancestor in their past to malign. I find that generally disgusting. But the actions of a few of my family during this terrible year [1955, the year of the murder and trial], when faced with an easy cowardly choice and a hard brave one, left a terrible stain on our name. On my name.” Complicity of so many in so many ways haunts every page of The Barn.

When it comes to silence, memorials tell the story. I recently read a book about the “lost cause,” an academic book opening with a memorial. Thompson writes that “Memorials in my homeland had always been about forgetting.” How so? Kris and I, in South Africa, were once taken to the famous “Voortrekker Monument,” which celebrated the story of those who created that nation’s famous apartheid system. A memorial for Emmett Till would shed light on the story; it has recently been erected. Too many memorials silence that story by recalling the lost cause. Countless city squares in Mississippi embody statues of Confederate soldiers.

Who was in that Barn?

“Emmett Till was there.

J.W. Milam was there.

Roy Bryant was there.

Leslie Milam was there.

Carol Bryant told her family that her brother-in-law Melvin Campbell was there and she claimed he actually pulled the trigger.

Too Tight Collier was there.

Henry Lee Loggins was there.

J.W. Milam told an acquaintance that a man named Hugh Clark was there…. Elmer Kimball” and maybe/probably his son, according to some. As many as fourteen were there. Two were put on trial (J.W. Milam, Roy Bryant). The court sided with the murderers. “A cult is built on believing the absurd if the absurd justifies the cult.”

The acquitted may have been released but they immediately became “living mirrors” of the Delta’s deep complicities in white supremacy and violent racism. “Responsibility for the status quo falls on the heads of every single person living benefiting from the status quo.”

What parts of the story were known were kept alive by Emmett Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, and by her pastor, Wheeler Parker Jr., who was with Emmett Till when he was kidnapped from the home, and Gloria Dickerson. And that’s not to ignore those who held the story tight for years, if not decades, like Willie Reed (Louis), who saw the truck, the men in the truck, and heard the cries of Emmett Till.

The complicities are generational, statewide, regional, and national.

Thank you Scott.

Tragically important recollection.