The Other Evangelicals

The Other Evangelicals

The major outlet for official evangelicalism has been, and probably will continue to be, Christianity Today. But the definition of “evangelical” that shapes the meaning of “evangelicalism” requires a Who question as much as a What question. That is, Who defines who is an evangelical? And only then What is an evangelical? I don’t want to pound too hard on this drum yet, because a brand new book will give us opportunities to process the drumming, but I will say up front and central that the Who question means Who’s got the power to do the determining and defining?

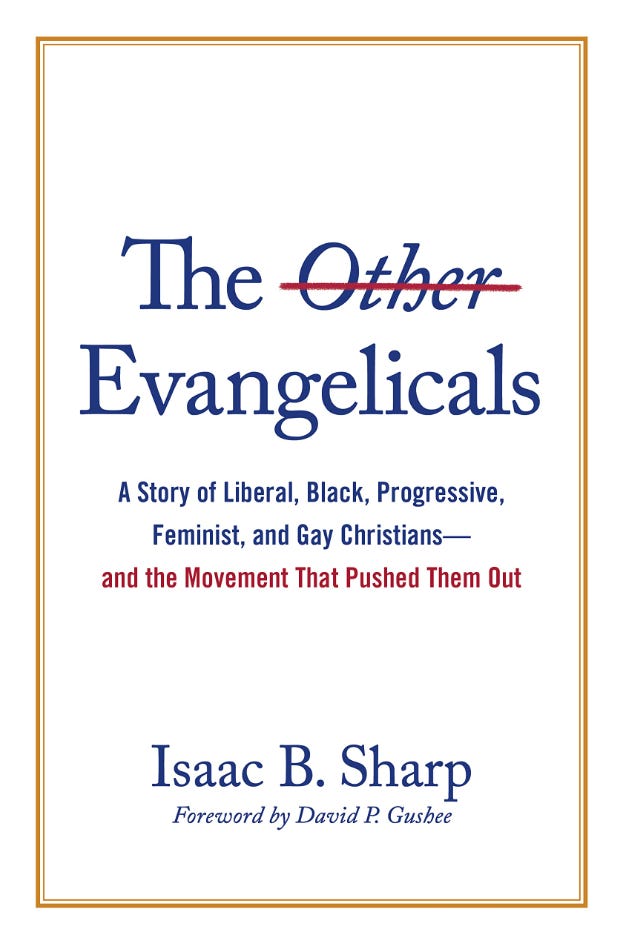

The new book is by Isaac B. Sharp, and it has the clever title The Other Evangelicals. Clever title already. The subtitle provides the answer of who these others are: A Story of Liberal, Black, Progressive, Feminist, and Gay Christians – and the Movement That Pushed Them Out. As you can see, Sharp’s very accessible dissertation covers lots of ground, and all of it bumpy and ditch-filled for someone. For me the issue is how history fits his conclusions. Because of the nature of these topics, I will make the rest of the posts about this book only for the paid subscribers.

His Introduction is a gold mine of the history of historians discussing evangelicalism.

First, Jimmy Carter (1976) and George Gallup Jr (1976) introduced the American public to the term “evangelical” in a way that took off. Carter’s own testimony mentioned his born again experience and Gallup, an evangelical himself, began the history of statistics about evangelicalism and counting evangelicals. His numbers told the story that evangelicals mattered in the American public. But Gallup began to define the meaning of evangelical itself. Polling, to put it bluntly, framed who was an evangelical: born again, Bible as the actual word of God, and evangelistic outreach.

Second, George Marsden, the father of historians of evangelicalism, put the rise of evangelicalism with Billy Graham on into a social and historical context. It was “transdenominational, decentralized, and popular… with no official magisterium.” He posed the (neo)evangelicalism over against the fundamentalism out of which it came. His Fundamentalism and American Culture reshaped and still often shapes the discussion. Fundamentalism responded, or overresponded to modernity, and evangelicalism toned down the response to a more intellectual cultural engagement. One major emphasis, and one I grew up in, was the attempt to minimize the fundamentalist heritage of evangelicalism. Marsden’s work then saw others join the discussion: Joel Carpenter, Nathan Hatch, Mark Noll, and Grant Wacker.

Len Sweet then reminded everyone that these histories of evangelicalism had an existential element to them, namely, that the historian wanted to define himself out of fundamentalism and reveal a more robust evangelicalism without fundamentalism. Think Carl F.H. Henry. Here’s a major point for Isaac Sharp: a “tendency to hold up one stream of the historical evangelical tradition as the sine qua non of true evangelicalism.” Such a move led to a defined, canonical view of evangelicalism. In spite of the battle between George Marsden and Donald Dayton over which group best explains evangelicalism – Reformed/Calvinism or Pentecostal/Holiness – the challenge was met as much by argument as it was by, well, power. The former view became the “normative” understanding of evangelicalism. Yet, some argued for a synthesis of the two sides of that defining argument.

Third, Christianity Today joined forces with Gallup in 1978, resulting in a set of categories that defined Who was true and Who was not. That is, attending church, reading the Bible, Jesus as God, faith in Christ is the only path of salvation, Bible as inerrant, and personal experience – with two kinds: the orthodox and the conversionist. Barna th en jumped on board. By the time Barna’s categories were used to figure out Who was in or not, about 12% met the categories.

Fourth, Who are these evangelicals? Are they antimodern conservatives or an embattled lot that is thriving? Enter James Davison Hunter’s work that eventually concluded evangelicalism was slipping from its main commitments while Christian Smith argued that, because evangelicalism was embattled, it’s embattled condition led to strategies of survival and cultural tools that permitted it to thrive.

Did you remember that there is no magisterium to decide? (That’s part of the game of this entire discussion.)

Fifth, a perception of evangelicalism turned into a reified understanding since the 1970s and 1980s or so. It includes (1) beginning with fundamentalism, (2) it formed into the post WW2 neoevangelical coalition that separated itself from fundamentalism, (3) midcentury America led to a powerful network of evangelical churches, leaders, and institutions, including publishing houses, (4) the Religious Right formed into a political wedge, and (5) one argues the movement is either waning or waxing.

Sharp’s question is how this conventional history became conventional. Polling was important, and polling ignores nuances and diversity and the pluralism of the so-called evangelical tradition.

Hear this:

… the neoevangelical coalition was undeniably successful in at least this sense: they invented an evangelical identity that caught on in the 20th century American context in a major way” and “by staking a claim for a new identity space called evangelical, such leaders were simultaneously claiming the power to define evangelical identity however they saw fit.... The leaders of the 20th century evangelical movement were able to secure their understanding of evangelicalism as the mainstream version. In so doing, their definition of evangelical identity became canonical.

The Who question becomes the big one.

There have been, of course, critics other than Don Dayton. In particular, Daryl Hart has been a major voice in contending evangelicalism was and is a chimera, an abstraction, and as such it cannot sustain robust Christian theology. It became lowest common denominator stuff. It lived in a “minimal consensus.”

Sixth, what then about the other evangelicals? The Who that defined evangelicalism masked the fragility of a movement that was inherently diverse. The identity definitions were too pragmatic to hold the group together or to meet its challenges.

So here’s a take-home framing by Sharp:

The history of mainstream 20th century evangelicalism is best understood as a story about how a group of mostly self appointed evangelical leaders—including theologians, historians, ethicists, famous pastors, popular authors, and political activists—transformed the generally conservative version of evangelical identity invented by the mid century evangelical coalition into a proprietary religious identity marker with an increasingly specific set of explicit criteria and implicit connotations.

This group drew a circle around itself and said, “What a good boy am I.” But it has since struggled without success at boundary maintenance.

Those inside are for them the winners but Sharp is about to tell us the story of the losers, the other evangelicals who got pushed out.

Join us for the discussion of this book.

I’m looking forward to this... my parents are solidly in this evangelical world, which has shifted from the evangelicalism of my childhood into something much more political and overtly fundamentalist, at least to them.

Thank you for this insight .