The Reading Life, Part 2

This continues the Substack from last week, in which I talk about my reading life and the search for great books that speak to the soul and about human life.

This drifting from one author or book to another is desultory reading, and is exactly how reading occurs for me. The knack, if you want to hit on the greats of history (or indulge the vanity of sounding intelligent), is to read the right books, listen to their connections, and come to know, as only readers come to know, the author himself (which in the names so far have been males, but read on). J.D. McClatchey, in his introduction of the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, says that Millay “wrote from the bedroom, not the library.” I know (popular) writers who seem to write from the living room, or the kitchen table, or the coffee shop, or even the summer vacation cabin, but great writers set pen to paper in the library and know the discussion, like the Delphic oracle, whereof they speak. Not that they need footnotes or books piled all over their desk.

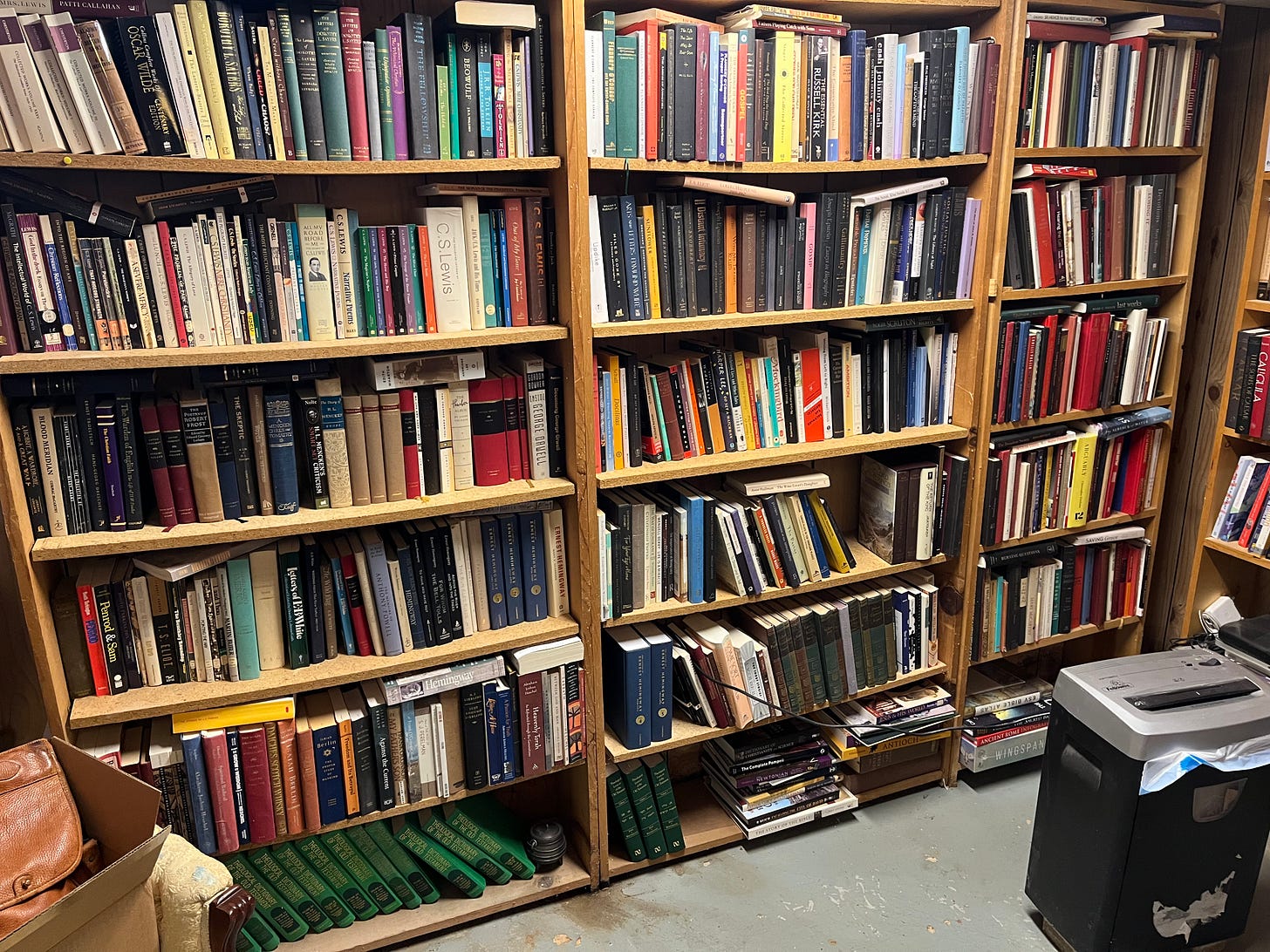

The image is of some shelves of what I call “writers.”

How might you find the greats? Some will give you lists, as did Mortimer Adler, who designed with Mr. Ego Robert Maynard Hutchins The Great Books of the Western World. On campuses today, their efforts are an effrontery to the rising tide of younger scholars who think textbooks need to be apportioned into diversities, and I defend presenting alternative theories. You can’t squeeze liberation thinking or anti-racism out of Wayne Grudem. So you need to read Love Sechrest, to take but one example of excellence. Still, I find tallying syllabi to be a kick in the shin of intelligence. My sort of reading is too drifty and restless to worry about the niceties of trends. Besides, one of my favorite (female) writers, Dorothy Leigh Sayers, once said, “What is repugnant to every human being is to be reckoned always as a member of a class and not as an individual person.” Let me quote her again: “Indeed, it is my experience that both men and women are fundamentally human, and that there is very little mystery about either sex, except the exasperating mysteriousness of human beings in general.” And her book was titled Are Women Human? None moreso than Sayers herself.

I may never end her exasperation, but I do worry about finding the greats. Jacques Barzun has four intersections each great must pass in order to arrive safely home: thickness, adaptability, votes, and academic discussion. Perhaps he’s right. I would emphasize that the greats bring intense pleasure in their reading (and, this must not be forgotten, their re-reading). But, I have discovered one sure-fire method of finding the best books in a bookstore, or what the Romans once called taberna libraria. Go to Barnes and Noble on a Friday evening, just after dinner, and find the least inspected shelves, and there you’ll find the greats. People, from the looks of the store, read stuff by John Grisham and Robert Atkins and Tim LaHaye, but there is no shelf-pull toward Homer, Hesiod, Virgil, Dante, Shakespeare, Montaigne – and here we pass into the age of first names – Ben Franklin, Samuel Johnson, Jean Jacques Rousseau, J.W. von Goethe, Robert Louis Stevenson, or even those as recent as G.K. Chesterton, H.L. Mencken, Dorothy Sayers, James Thurber, E.B. White, George Orwell, A.J. Liebling, Isaiah Berlin, Flannery O’Connor, Joseph Epstein, Umberto Eco, James Baldwin, Edward Said, Lionel Trilling, Marilynne Robinson, Nancy Mairs, Joan Didion, Cynthia Ozick, Anne Fadiman, V.S. Naipaul, Maya Angelou, or Merrill Joan Gerber. Pause for a minute with this cumulus of great writers. You’ll find their prose siren-like, their topics humane and urbane, and their angles clever and insightful. And sometimes they are just plain fun to read. I am a sucker for the witty, and find myself wandering into the writings of James Thurber and Robert Benchley and S.J. Perelman and Anne Lamott.

There’s that joie de vivre in the former sorts, too – well, perhaps not in Mencken for he was more intent on scoring points. As Terry Teachout has shown in his superbly written biography of Mencken, that man’s sturdy pen had a sharp, serrated edge, and it began its work with after-breakfast cigars. It was Mencken who delighted in blowing (cigar-infested) fumes of cynicism on simple souls of faith. When speaking of the soul and the claim that it separates humans from beasts, Mencken fumed: “Well, consider the colossal failure of the device. If we assume that man actually does resemble God, then we are forced into the impossible theory that God is a coward, idiot and a bounder.” Let’s not follow his gaseous thought any further, for a few gulps of straight Mencken is plenty for the day. Instead, let’s admit that places in the bookstore where most people stand have books that tell good stories (people are buying them for a reason), and reveal secrets for living for the next week or so. But I’ve yet to find those authors struggle with life and death, with meaning and purpose, or with questions like “Who am I?” or “Who are we as a ‘we’?” or “What is God like?” and “How might I know God?” Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich probes those questions.

Such questions and authors who probe them, which now seems incredible to me, kept me from reading fiction. It is not that I didn’t appreciate the authors – I often read biographies of fiction writers – or that I didn’t think they had their day. But, you cornered my attention if you mentioned Homer, Virgil, and Dante, even you claimed they wrote fiction. I tricked myself by holding the definition of “fiction” until modern times. Old fiction was non-fiction for me, so I called it philosophy or theology. Ancients for me were iconic – they ushered me into another (higher) world. My problem is that I don’t like authors to think they can just plain make things up, and do what my mother called “telling a story.” Professional golfer John Daly, who rarely does or says anything intelligent, accidentally stumbled from a fairway onto a stage of reporters and commented ever so accurately that he didn’t like fiction because, “after all, none of it is true”. Depending, I guess, on what you mean by “true”, but the floppy-haired, droopy-faced golfer was onto something. At least at the time I thought he was. Why, I have asked myself for nearly 30 years of serious reading, why read those who play pretend when I can read those who tell the truth? Fiction, to quote the words of one who did write a bit of fiction (Frank O’Connor), “covers every reality with a sort of syrup of legend.” I only felt uneasy about my lack of reading fiction, but like political opinions, it quickly passed. Until about ten years ago when I too many of my friends were talking fiction. So I searched for those whom I believed would point me to good fiction writers. It began with Willa Cather, and I’ve been stuck on her since. I’ve read all her novels, some of her short stories, and a few of the books I’ve read twice. Then Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Wharton, Steinbeck, Harper Lee – I’ve got the habit now of reading at least a few pages of fiction before I fall asleep.

I confess I always have read some fiction – I read, annually, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol and Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. I like both of them; I am sentimental at Christmas and I am always in need of a good search-and-find-but-then-lose story. I don’t like Dickens’ style, but I find Hemingway’s tasty and zesty. Kris and I last summer sat in a restaurant in Petoskey Michigan a few feet from where they said Hemingway sat and drank and ate and drank and sat. At a colleague’s request, I read Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose (an overcooked blasting away at the Catholic Church and its power over truth, Eco’s edges have [to use Thurber again] “lost their certainty”), and some Russians – I got half way through both Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (I’ve read much better presentations of theodicy in non-fiction; I liked Zosima a bit, but he was not real and I got bored with him) and Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago. For some reason, the Russians (even if they can spell) have more endings and changings of personal names than a Greek verb, and I seem to fall asleep on the Russian fictionalists every time they take me on a train ride across their desolate, snowy, gloomy, frigid landscape. Nabakov, in his high-style (almost rococo) autobiography, Speak, Memory, does tell of summer in Russia, and makes me want to go there, but I’d rather go other places in the summer – like to golf courses or to baseball fields or to Ireland or to Scotland. If the list gets any longer, I may wipe Nabakov from my memory.

Again at the request of a colleague, I altered my (otherwise enjoyable) desultory “plan” to read that southern lady’s To Kill a Mockingbird. It was not as good as Samuel Butler’s The Way of All Flesh, but neither was Butler as good as Matthew 23 or Micah 5. Novelists are not prophets, though they think they are. Sometimes they are prophet-like, but they just don’t have the moral grounding to give a full-blown answer, and neither do they have the thunder of Zeus. Take Mark Twain, that boyhood idol of mine whose home in Hannibal, Muzera (as they say it) is one of my favorite haunts. Twain takes on slavery and racism, but he is so interested in entertaining and selling books (he managed his own money like an addicted gambler at a casino) that he has no answer and sinks the argument with a farcical vaudeville act on Huck’s raft. He’s best in telling stories, like Tom Sawyer. And Tom Sawyer, like the Calvinism he resented, “ain’t all that great”.

Loved this a lot. “Novelists are not prophets.” Try these: I submit to you George Orwell’s 1984. Also, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, Lois Lowry’s The Giver, and Margaret Atwood. Bam.

Thank you