“…the truth that reading and its necessary twin, writing, constitute not merely an ability but a power.” --- Jacques Barzun

“Every old man complains,” so said Samuel Johnson, “of the growing depravity of the world, of the petulance and insolence of the rising generation.” Old Professors moan, like veteran Argive soldiers long back from Troy, about the privileges – hard earned ones – the young Professors have, like sabbaticals, computer support, and no longer needing to raise funds for the school. More often, though, they crab about the competence of young students to write clear sentences with good grammar and active verbs and concrete nouns. I agree with older generation. I am inclined, however, to think the Apocalyptic Darkness is not just round the bend for, as Robert Benchley once wrote, “the little legends on which we were brought up before the world grew dim and sordid” are just that: “little legends.”

I am also inclined to think business and technology graduates, whose minds are kept away from culture and who think education is primarily “know-how” rather than cultivation of culture, are spelling-challenged and grammar-deficient. How so? Because a business in our local mall used to run a “Collectable” shop and a recent ad at the same mall spoke of some merchant’s “6 Idea’s”. Paul, give me a drum roll … now hear this: that same “Collectable” shop has been purchased by “The Russian Gift & Collectible Shop” – I’m not tugging your tunic here. Russians, who have an alphabet with too many letters and novels with too many pages, have apparently learned through these native experiences to spell better than the former owners. These Russians, to adapt the words of Dorothy Sayers, “looked it [the spelling] full in the face, and said that it was the devil.” I thank ‘em for that.

A trip to the furniture department at Marshall Field’s on Michigan Avenue confirmed my concord with the curmudgeons. Those who make furniture are evidently business types, and not Humanities types. I was unable to find one chair comfortable for a reader – you know, the sort of chair that sits upright, with nice arm rests, and a short enough space from back to front that one has to rest one’s feet on the ground. In such a chair, the reader can easily lift a leg, cross to the other one, and make for a reading table. Such chair designers, I concluded, don’t read or they’d learn to make chairs comfortable enough for readers. Perhaps I am mistaken. Maybe they read e-books on planes as they bop across the nation to find cheaper labor or cheaper wood or cheaper fabrics. They don’t, however, have a leg up when it comes to making a reader’s chair.

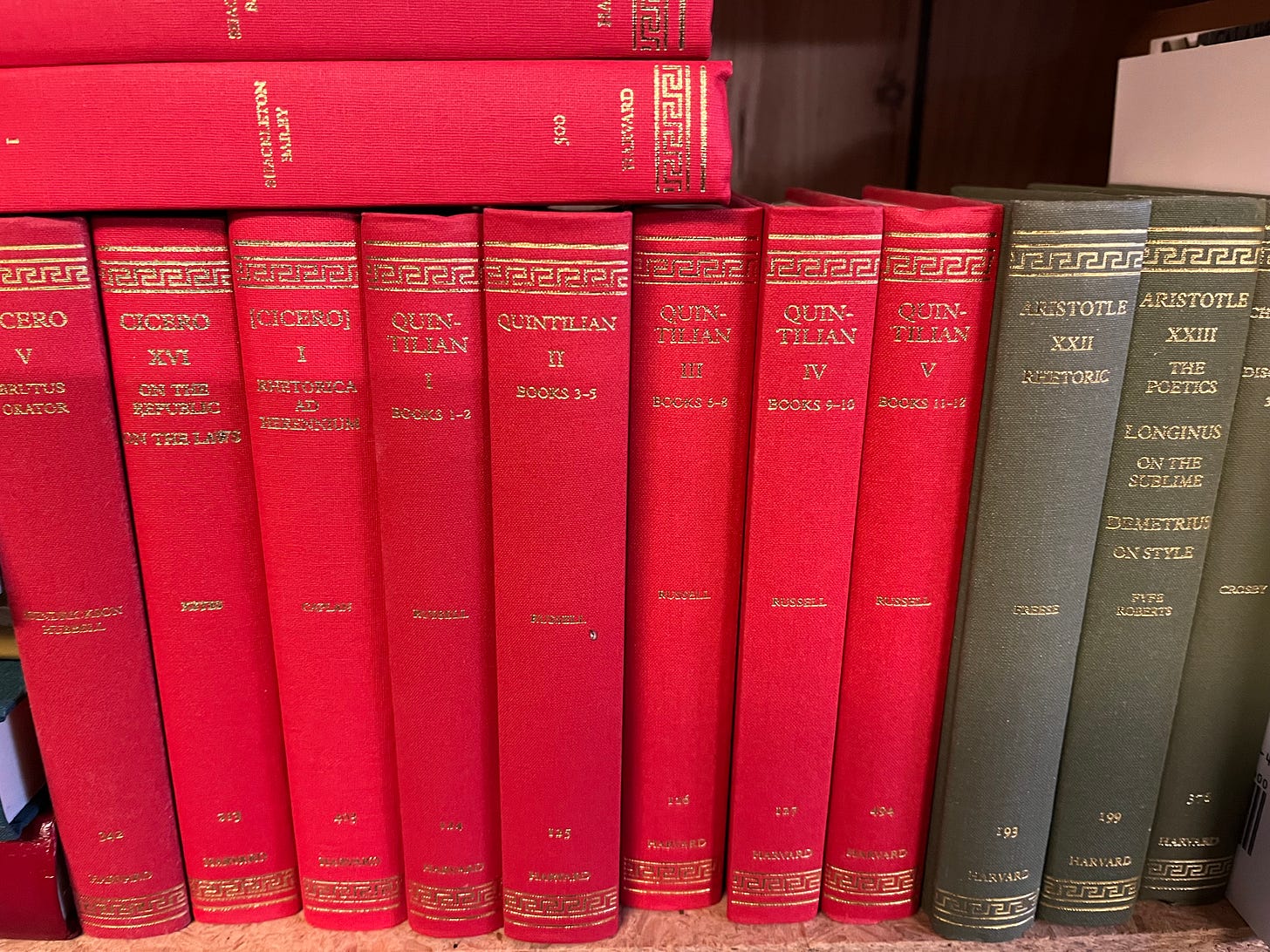

I have such a chair in my library, near my desk. It was given by my wife’s grandmother to us, and it looks grandmotherly (if not great-grandmotherly). It has been recovered three times since our marriage, and now sits in new clothes without its former dog-eared corners. Its green, sometimes a bit gray, has become lustrous brown and has only a gentle silt of wear. It was, as the book title has it, slightly chipped, but still standing. It now sits proudly in our living room. It is for reading and for readers who like reading. It is not, to adapt the title of another book, for slouching towards the TV. Upright, curved slightly, nice arm rests, just enough room for the posterior but not enough to go slumping. Chairs like this are for readers of good books and good books usually come with good bindings – clothbound, knitted together by someone who cares what books look like, printed with fonts that breathe class, and surrounded by covers that are proud to be covers. Everyman’s Library, in spite of its old-fashioned name, has such an old-fashioned binding. So do the Loeb Classics, pictured above. “Hardback” is a bad expression; I don’t want books with anything hard and books don’t have “backs”. Books have spines, and (cloth) boards, and bindings. Perhaps paperbacks have backs, but they are not very often welcome in my chair.

I am here put in the unusual condition of being an author who prefers clothbound, but whose publishers don’t always value his talent enough or think his longevity sufficient to encase his ideas in clothbound editions. When my first clothbound arrived on our doorstep, I sat in a chair on the back porch with one of my books, lit a Cuban Montecristo, poured a short glass of something special, and read one of my books appropriate to the chair. I’ll not relinquish my principles: clothbound over paper, enduring binding over cracked glue. While maintaining those principles, I take comfort in the light-hearted claim of John Maxwell Hamilton, who provides in his Casanova was a Book Lover a gentle, if journalistic, romp through the publishing world: “The university credo is that faculty members are expected to write books that no one wants to buy in order to keep their low-paying jobs.” Professors have never read the words of Samuel Johnson: “what is of most use is of most value.” Had we heeded those words, we might have learned to write things that are not only intelligent, but also useful. But, to re-use the words of James Thurber after reflecting on his early career in journalism, if I thought about my life of research and writing and “put it all together … I don’t know what it comes to, but it wasn’t drudgery.” Professors know students aren’t drudgery, but too many professorly tasks and assignments are.

Let me lay my cards on the table now: I read what I want – as often as I can. You see, my reader, I’m a professional when it comes to reading: I read for an occupation. I teach seminary students, and that means I have to read to stay one book ahead of them – which, frankly, isn’t (as the curmudgeons declare) as hard as it used to be. But that sort of reading I do is compulsory – if a new book comes out on Jesus or the early Christians (and plenty do come out), I have to read it because that is my job. But, apart from the compulsory reading (and it is not onerous), as often as I can I read what I want. The right word here is “desultory”. Desultory can hold hands at times with “indolence” which, in the words of Samuel Johnson, “is in every man’s power,” but need not. Desultory reading can be hard work for, as C.S. Lewis once wrote, “… literary people are always looking for leisure and silence in which to read and do so with their whole attention.” People of leisured silence become the good writers, the writers who probe the human condition, who put on paper words that make the heart jump and who, whenever they can, turn writing into the joie de vivre.

My heart, for instance, jumped when I recently re-read Dante Alighieri’s (whom a Texan friend refers to as “Danny, Ally, and Gerry”) The Divine Comedy, which title takes some brushing up against some intelligent folks to comprehend. I liked Dante, but he led me to read Virgil (whom the urbane spell as Vergil), who wrote the even more noble The Aeneid. Virgil beckoned me to begin again with the great epics from Greece, Homer’s The Iliad and his even better The Odyssey. I read the Oxford History of the Classical World chapters on Homer first. That made me want to read the next chapter, the one on Hesiod and Myths, which led me to read Theogony and Works and Days, and so on. Virgil, Homer, and Hesiod – a pagan’s trinity mediated in priestly fashion by a Roman Catholic (Mr. Alighieri, I mean). Wonderful books, breathtaking grasps of the relationship of the human and the divine, bold and brazen in their attempts to wrap their minds around life as they experienced it. They charm in their depiction of tragic characters – like Agamemnon sulking in his boat, or Ajax angry enough to take on a Troy, or Zeus so ticked off by human effrontery that he conspires to send them all to Hades. Hesiod stands a bit short next to the other two tall drinks of water, but he stands proud. (And he’s not chipped at all.) Sophocles didn’t get enough of Ajax in Homer’s epic, so he made up some more and put in plain (Greek) prose the enormity of his pride and added some creases to Ajax’s forehead of worry about glory: so devastated was he in not getting the arms of Achilles at his death that he buries his sword point up and falls on it. The story is gory; but the theme is larger than life, and so Homer and Sophocles have pinned a flower sustained by ambrosia on Ajax’s shield. What we do learn about life from Ajax was stated by the Irish writer, Frank O’Connor: “The leader is a man so great that he [unlike Ajax] doesn’t have to be jealous.”

You're right, Scot: they're not "hardbacks"; they are "casebound" with boards and spine and, in the modern era at least, preferably, Smyth sewn bindings. Every casebound book we produced at Eisenbrauns as Smyth sewn—and many of the paperbacks (so-called) were as well. Too many books nowadays have the intellectual and physical half-life of a Starbucks coffee.

Good to see my old friend has not lost his love for books or reading or learning