When I was a college student Marabel Morgan’s megaseller The Total Woman appeared, defining a woman as follows (hang on, this is for real):

A total woman is not just a good housekeeper; She is a warm, loving homemaker. She is not merely A submissive sex partner; She is a sizzling lover. She is not just a nanny to her children; She is a woman who inspires them to reach out and up.

That was 1973. That book envisioned the ideal woman for the ideal evangelical man.

That book appeared while the Equal Rights Amendment was being debated and it appeared when many masculinist men thought feminism might crack the foundations of society. Evangelicalism was the vanguard in reacting to feminism, arguing over and over that women are designed for marriage – wives and moms – and not for leadership in the church.

Here’s a truth:

Throughout US American history, the majority of the Christians sitting in the pews of the nations churches have been women, and evangelicals have been no exception. The majority of history books about those churches full of women nonetheless have been both full of and written by men.

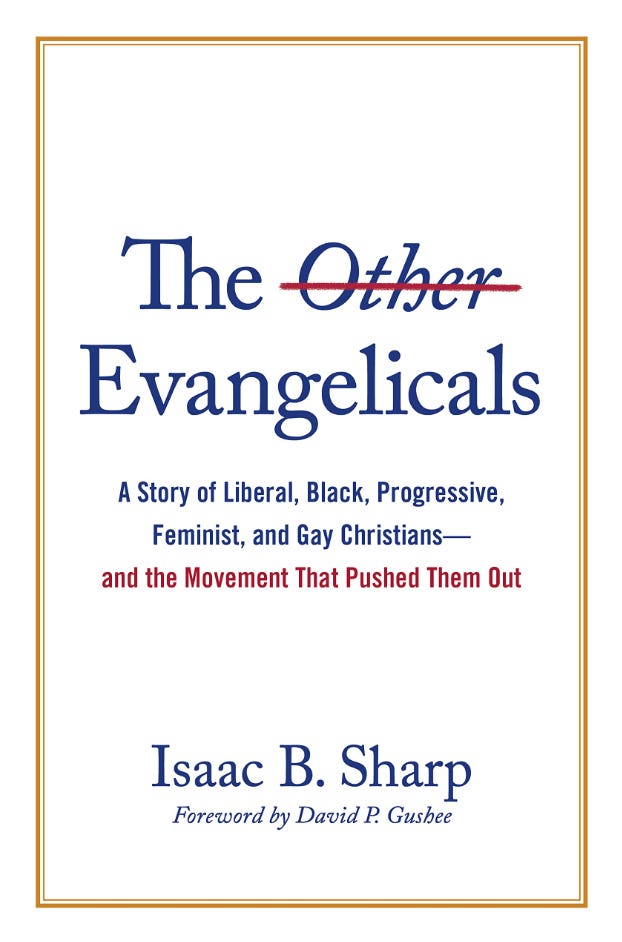

We are looking at Isaac B. Sharp’s book, The Other Evangelicals. So far his thesis has been sustained: evangelical gatekeepers of the mid 20th Century pushed out liberals and Blacks and progressives. In today’s Substack we listen in on Sharp’s excellent storytelling capacities to how the evangelical feminists rose and then got pushed out by the same gatekeepers. The male-centeredness of both evangelical leaders and evangelical theology corresponds rather neatly with the near exclusion of women at the table when the gatekeeping lines were being drawn.

Christianity Today’s founding leaders were all men; so, too, with the NAE; Fuller Seminary struggled for years to admit women in, first, as students in the BD (=MDiv today) and then as professors. Look up Rebecca Price.

Three strong women leaders provoked the evangelical feminist movement. Each grew up in stereotypical evangelical homes; each attempted to play that game; each broke free; and they found one another to form the Evangelical Woman’s Caucus (EWC).

Letha Dawson Scanzoni: she discovered her gifts for leading, speaking, and especially writing but heard the voice of those who thought a woman’s place was in the home. Once reading two essays in Eternity magazine, one egalitarian by HH Kent and the other quite aggressively patriarchal (Charles C. Ryrie), Scanzoni wrote an essay that became “The Women Issue” and she was off and running with essays and responses and teaching, but what got her into the limelight was an essays arguing against patriarchy and for partnership in marriage. Her editor was Nancy Hardesty…

Nancy Hardesty; Youth for Christ; Wheaton; editor; English teacher at Trinity College (Deerfield); then she and Scanzoni wrote THE book, though they had a dickens of a time getting a publisher: All We’re Meant to Be (1974).

Virginia Ramey Molenkott. Plymouth Brethren; Bob Jones; married to a difficult man; eventual PhD in English – and she began to push and push for an egalitarian ethic. Sharp writes most about her in this group of three evangelical feminists.

Opponents included Marabel Morgan and especially Elisabeth Elliot.

The Total Woman approach was opposed then by the Total Women egalitarians. At the heart of the Scanzoni-Hardesty book, All We’re Meant to Be, was the important distinction between inspiration of the text and the interpretation of the text, with interpretation needed to be seen for what it is not, that is, inspiration. That book became the vanguard book of the movement.

The EWC formed out of the well-known Thanksgiving Workshop, which created the Chicago Declaration I mentioned in the last post about Sharp’s book. Hardesty pushed and pushed for a statement about women in the Declaration and this was finally added:

We acknowledge that we have encouraged men to prideful domination and women to irresponsible passivity. So we call both men and women to mutual submission and active discipleship.

Billy Graham would not sign the Declaration because of this statement about women. The EWC formed independently out of this Thanksgiving Workshop, which itself became the Evangelicals for Social Action. The EWC then took off on its own and fizzled on its own, partly because of internal division and partly because of a lack of funding. The internal differences occurred over the acceptability of homosexuality (Scanzoni and Mollenkott wrote an affirming book called Is the Homosexual My Neighbor?), and the EWC had a fair number of lesbians in the group. Eventually one group broke out and became Christians for Biblical Equality, led originally by Catherine Kroeger. I’m getting ahead of Sharp’s story.

A major scholar chose to stand with the EWC. His name was Paul King Jewett who wrote a book that both defended equality and disagreed with inerrancy. His book is Man as Male and Female. I remember reading that book just after its heyday. So irritated was Harold Lindsell over Jewett’s degrading of inerrancy that Lindsell wrote his diatribe, The Battle for the Bible, which I read when it came out and before I read Jewett. Lindsell warned everyone that those who softened on inerrancy would slide down the slippery slope.

Alongside the egalitarians was Patricia Gundry who, at Moody, wrote Woman Be Free, and her public speeches got her in trouble, and her husband Stan, who left Moody as a prof of theology to become a longstanding major editor and publisher.

As with liberalism, Black evangelicalism, and progressivism, evangelical feminism was on the rise into acceptance as part of the evangelical movement.

Until the gatekeepers said No and gave them a label of being nonevangelical and other terms.

The gatekeepers, beside those already mentioned, included Wayne Grudem and John Piper, who produced Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood. Grudem led his own charge through ETS and a series of books. They organized into the Danvers Statement and then formed the CBMW, which remains a vital force in American evangelicalism to this day. Regarding their big book, Sharp says

For the rest of the 20th century, the book, its authors, and the organization they represented became massively influential in the US American evangelical world period from its late 1980s invention forward, complementarianism spread like wildfire. Numerous groups, dozens of major evangelical organizations, and countless evangelical leaders began emphasizing its antifeminist, nonegalitarian interpretation of a divinely mandated sexual hierarchy as the default evangelical view on sex and gender.

That view is not the instinctual association with the word “evangelical.”

Back in the early 70’s, my sisters and I called Morgan’s book, The Totalled Woman! That is exactly how we perceived it. It was so unrealistic even for us young Christian women of the 70’s.

Ι seem to remember that Marabel Morgan suggested to women that they greet their husbands, who were returning from work, wrapped in Saran wrap, and nothing else. It has been 45 years or so, I might have this wrong.

I do have a thought that I have not seen dealt with by any of the complementarian group. Hierarchy was established in Genesis 3. One of the consequences of "the fall" is that God says to the woman is that he will RULE over you. Which in the English text is exactly what the couple are told that they will do with regard to the fish and birds (1:28). In other words, because of sin the man will treat the woman like an animal. Before I get corrected based on the fact the two different words are used (רדה and משׁל ) I would suggest that the words are synonyms based on their usage in 1Kings 4:21 and 24 where the same two words describe Solomon's rule over surrounding nations without any hint of distinction.