Was Abraham a Good Example?

Gen. 22:1 After these things God tested Abraham. He said to him, “Abraham!” And he said, “Here I am.” 2 He said, “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains that I shall show you.” 3 So Abraham rose early in the morning, saddled his donkey, and took two of his young men with him, and his son Isaac; he cut the wood for the burnt offering, and set out and went to the place in the distance that God had shown him.

The challenge is for the reader and can be asked in a question:

Why the silence? (In those italicized words.)

Why no protest?

Protesting and lamenting sin and injustice are thoroughly biblical. Why the silence?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binding_of_Isaac#/media/File:Sacrifice_of_Isaac-Caravaggio_(Uffizi).jpg

So many gaps in Genesis 22. So many questions. Our imaginations are stimulated to the highest levels in reading this chapter. Intentionally so.

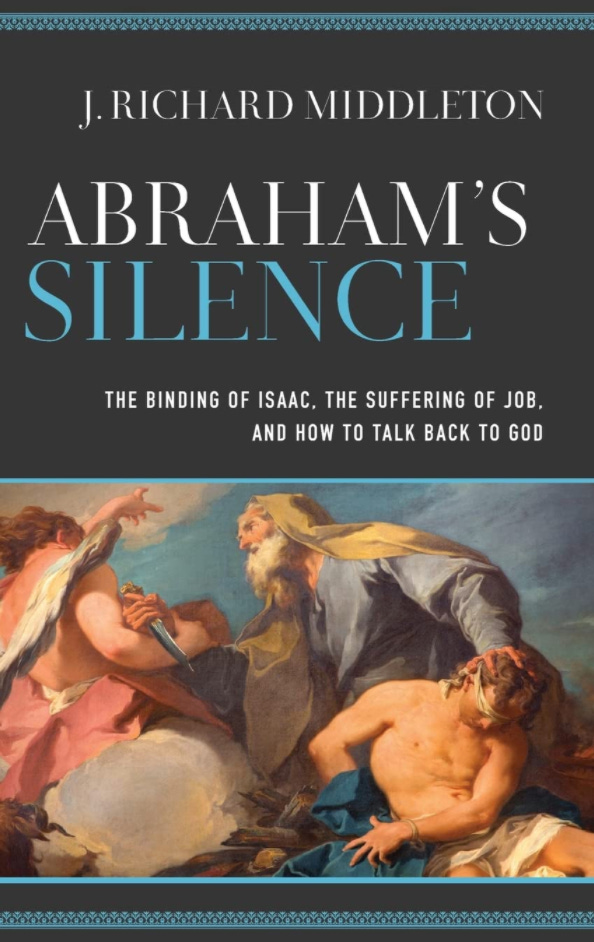

Long ago I learned from reading Meir Sternberg and Robert Alter to ask about the textual gaps in such texts, and J. Richard Middleton explores all the gaps in Abraham’s Silence.

The details are so many that only a sketch can be given here. What I want to do is give you the big ideas of what Middleton thinks of the silence of Abraham.

[For more newsletters like this, please:]

In this text it is “God” (Elohim) not YHWH who tested Abraham. This is unusual, and could be a distancing expression. A messenger of YHWH, however, stops the sacrificial act (cf. Gen 22:1, 11). Why the change?

Isaac’s relationship to Abraham, or vice versa, is plumbed at length in this book: in essence, he thinks their relationship is dysfunctional as measured by the textual details. They do not talk on the way there; and Isaac all but disappears after this event; he does not come down the mountain and does not accompany Abraham back. Isaac’s not given a separable story in Genesis that we do find with Abraham, Jacob, and Joseph. Middleton suggests Abraham favored Ishmael over Isaac; he thinks Isaac picks up the idea that God is the One to be feared (all this comes from his careful reading of the text). And “whom you love” he thinks could be translated “You love him, don’t you?”

Perhaps most provocatively, Middleton thinks God is testing Abraham about whether he loves this special son Isaac.

Is Abraham’s silence exemplary?

Abraham’s narrative arc in Genesis: What view of God did Abraham have? In Genesis 18 Abraham whittles it down to 10 survivors but Middleton thinks he does this in a way that does not plumb the depth of God’s mercy, love, and grace.

Middleton seesproblems in the traditional reading: (1) How is this a model for commitment? (2) Why did Abraham need to happen? There is no clear evidence of a special relationship of Abraham and Isaac.

Middleton thinks Abraham is being given an opportunity to prove his love for his son. He could have spoken up but he is silent. Then Isaac all but disappears. Even more, Abraham is being tested about his perception of God’s own character. Isaac ups the ante from Lot to Abraham’s own son. Abraham is silent.

Isaac learns not that God is a God of grace and mercy but one to be feared. Notice “the God of Abraham and the Fear of Isaac” (31:42). Isaac is distanced from his father from this point on; Sarah, too, is never close to Abraham – perhaps not even living with him – from this point on. It is a “broken family.” It was not Abraham who stopped the knife but an angel sent by the covenant God.

A big challenge to Middleton’s view are the words of the angel that seem to confirm Abraham as exemplary (not to ignore the positive view of Abraham’s Aqedah in much of Judaism and the NT). He probes how to see these words.

“By myself I have sworn”: God steps in because Abraham’s response was not as complete as it could have been. He thinks the ram was behind Abraham and, quite provocatively, he is not convinced Abraham had embraced the idea of God providing a ram instead of his son.

A sketch, for sure, without all the details, but you can get the big ideas from the above.

Middleton thinks Abraham did not in fact pass the test of Genesis 22. He could have protested for his son and his love for his son; he could have interceded; he could have had a more robust faith in God’s provision; he thinks he “just barely passed the test” of God’s character.

I've often considered how powerful a role art has played in my understanding of this story. Images of Abraham and Isaac inevitably raise for me the question, "How old is Isaac?" Is he a young boy, like in Michelangelo, his gaze locked on his father's with that up pointing finger poised midway between them? Or is he hairy, bearded and grown, like in some 19th C Ashkenazi art? I tend for the latter understanding. Reading the text somewhat literally, Isaac is in his late 30's when this story takes place. So for me, I'm not so interested in what Abraham is thinking, as I am in what Isaac is thinking. Silently reproachful? Willing participant and equal partner? It is telling, as Middleton points out, there is no story that has Isaac coming back down the mountain and going home to live peaceably with his folks...Having said all this, I'm just starting the new translation of Fear & Trembling and it's gonna take more than this book to shake me loose from Kierkegaard.

I think the way we interpret this passage depends on what sort of people we believe God wants us to be. Is God looking for people who will submit no matter what to an instruction they believe is from God, whether it's an audible voice, a thought, a Bible verse, advice from a Christian leader, whatever - or is God looking for people who make every effort to be people of good character and good values and who will question that which goes against their values or asks them to act in ways which betray their character no matter what the source? I contend that the latter is safer for human communities than upholding unquestioning submission as the ultimate act of faith, because how can we know it is God asking us to submit, or as Middleton points out, even if it is, why would we believe this is a test of faithful unquestioning submission rather than a test of whether we will speak up or say no when something doesn't make sense, rather than betray our values? I believe this whole discussion is good because implicitly it is saying, yes, do question, don't just accept things. Because I believe to do so is our human responsibility.