Defining the terms

By Karen Fletcher Smith

About a year ago I sat listening to a sermon in which the preacher began to describe theological terms concerning men and women in the church. While not the focus of the sermon, he was describing the different views on women and the theology around this movement. He went on to say that some believe in complementarianism that says men should be the head of the house and the church, and that others, called egalitarians, believe that women should rule everything.

[SMcK: this post is in our series on Heather Matthews, Confronting Sexism in the Church.]

I was stunned. I still am if I’m honest. I have spent the last three years of my life studying in seminary, specifically women and theology, and I have never heard someone define egalitarianism this way. Not only is it academically misleading, but more importantly it reveals a dynamic of power at the heart of these definitions.

When theological terms are defined using a hermeneutic of power, things get weird. I have been digging into the gospel story this week, specifically Peter’s interaction where he rebukes Jesus. Matthew sets this scene in chapter 16. After reading through this text multiple times and discussing with trusted friends, what I ultimately see is the battle of a man-made power system vs the kingdom God, the Kingdom of Peter vs the Kingdom of God.

Jesus in turn rebukes Peter and says, “you do not have in mind the concerns of God, but merely human concerns.”[1] Peter’s vision of the kingdom involved power, but likely a power that came at the expense of other people. Maybe Peter expected a political revolt at the expense of the Romans, maybe it was his selfish concern over his proximity to Jesus himself like James and John. Maybe it was concern that if Jesus was going to suffer and die that Peter himself might too. The point is, when Jesus centered others at the expense of himself, Peter objected. Was Peter’s heart after power or was it after the kingdom of God? In some ways it echoes the deceiver’s voice in the desert to Jesus, “you don’t have to do this. Step into your power and protect yourself.”

Jesus didn’t listen and freely gave up his power. This humility gave us the power of the Spirit for the flourishing of the kingdom. Peter read the scene with a hermeneutic of power, something antithetical to the kingdom of God. Jesus repeatedly shows us a kingdom that is upside down whether the first century, or our culture today. The kingdom uplifts the lowly and the outcast and there is no hierarchy.

Dream with me what a pocket of the first century church may have looked like. Holly Beers does this in her imaginative work called A Week in the Life of a Greco-Roman Woman.[2] Beers gives a captivating, fictional glimpse of a first century Ephesian woman’s life and a peek into the early church. In terms of power, the main character is shocked at the equality she finds in the church. This scene came alive for me as she describes a meal where masters are serving slaves because of the equality that Christ brings to the table. Can you imagine? What would this look like in our churches today?

Within the kingdom Greeks were equal with Jews, males were equal with females, slaves were equal with the free. That is what Christ came to bring down from Heaven. This is what Jesus was envisioning with the road to Jerusalem ahead of him. The way up is down, and the way forward was through suffering, for the benefit of all.

That is what Beers describes, and this is what egalitarians are after. I am aware that extreme feminist theology exists, but the vast majority of egalitarian thought I read through seminary is arguing for equality and mutuality, not matriarchy.

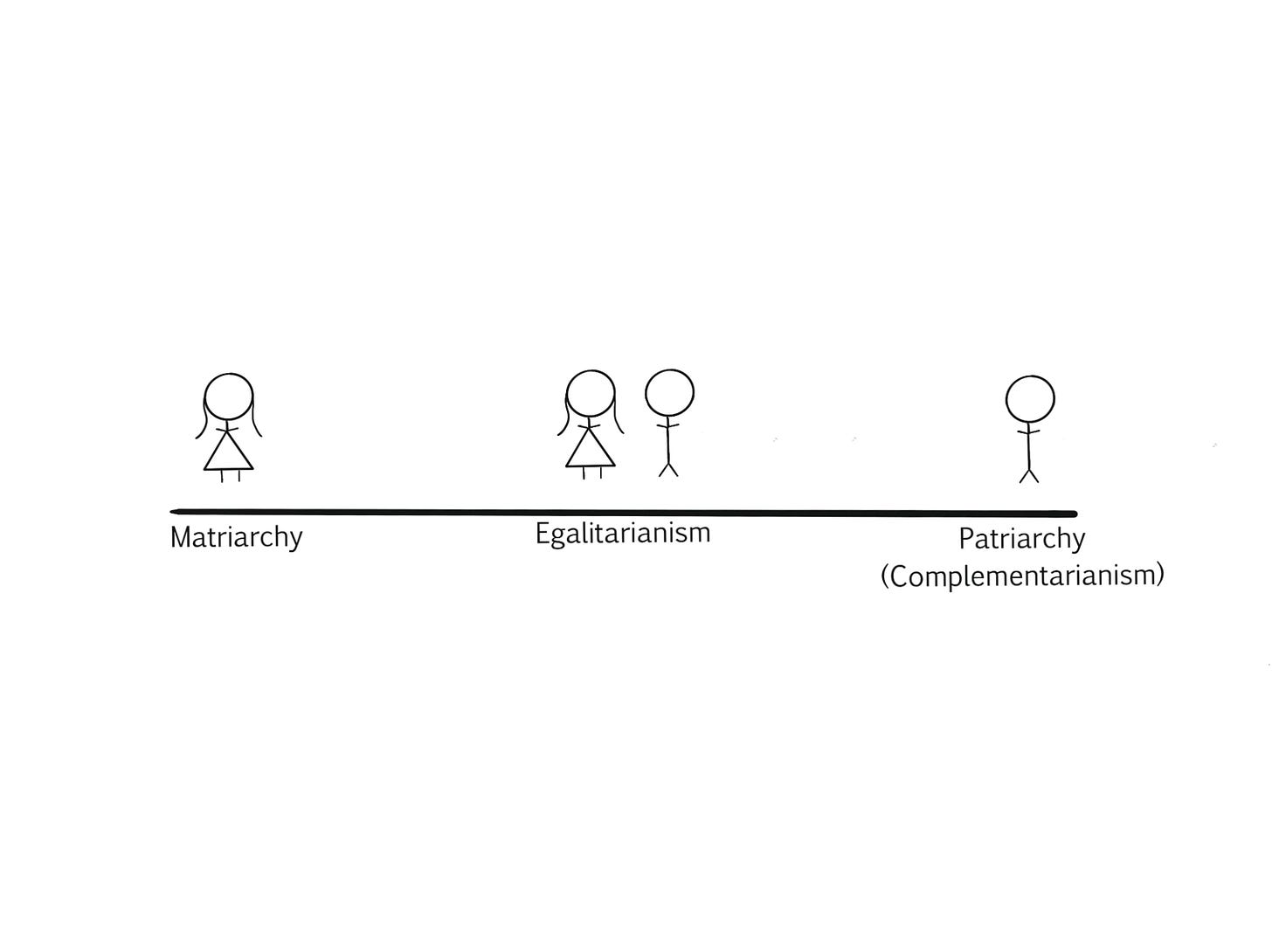

After hearing the sermon that day I made a quick sketch:

Egalitarianism is not the opposite of complementarianism, that’s matriarchy. So let’s define some terms:

Matriarchy as defined by Oxford Reference: “Literally, a community of related families under the authority of a female head called a matriarch; applied more generally to any form of social organization in which women have predominant power, there being controversy as to whether a matriarchy has ever existed, although there is no doubt that matrilineal societies have existed.”[3]

Patriarchy as defined by Oxford Reference: “Literally, a community of related families under the authority of a male head called a patriarch; applied more generally to any form of social organization in which men have predominant power.”[4]

Egalitarianism as defined by Oxford Reference: “A social doctrine that emphasizes the goal of equality among all members of a society—or, indeed, all humanity.[5] Theologically speaking, it sees all people as equal before God, with equal responsibilities and mutual submission.[6]

Now I realized these are social terms I am using to describe theological terms and yet the premise of the definition stands true.

Complementarianism is not in the Oxford reference so here it is as defined by the Danvers Statement[7], condensed from the Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: “At root, complementarians believe men and women are equal yet different by divine design, and that God’s design makes a difference in how we ought to live as male and female. Most concretely, complementarians believe the Bible teaches male headship in the family.”[8]

I would be remiss if I did not mention my complementarian friends that say they believe men and women are equal in essence but not in function or role as seen in the above definition. Spoon fed this theology in church; as a female, I wasted away on the nutritional deficit. If this was race, we were discussing, would we say the same, equal but not in function or role? That sounds a lot like the devastating concept of “separate but equal”.

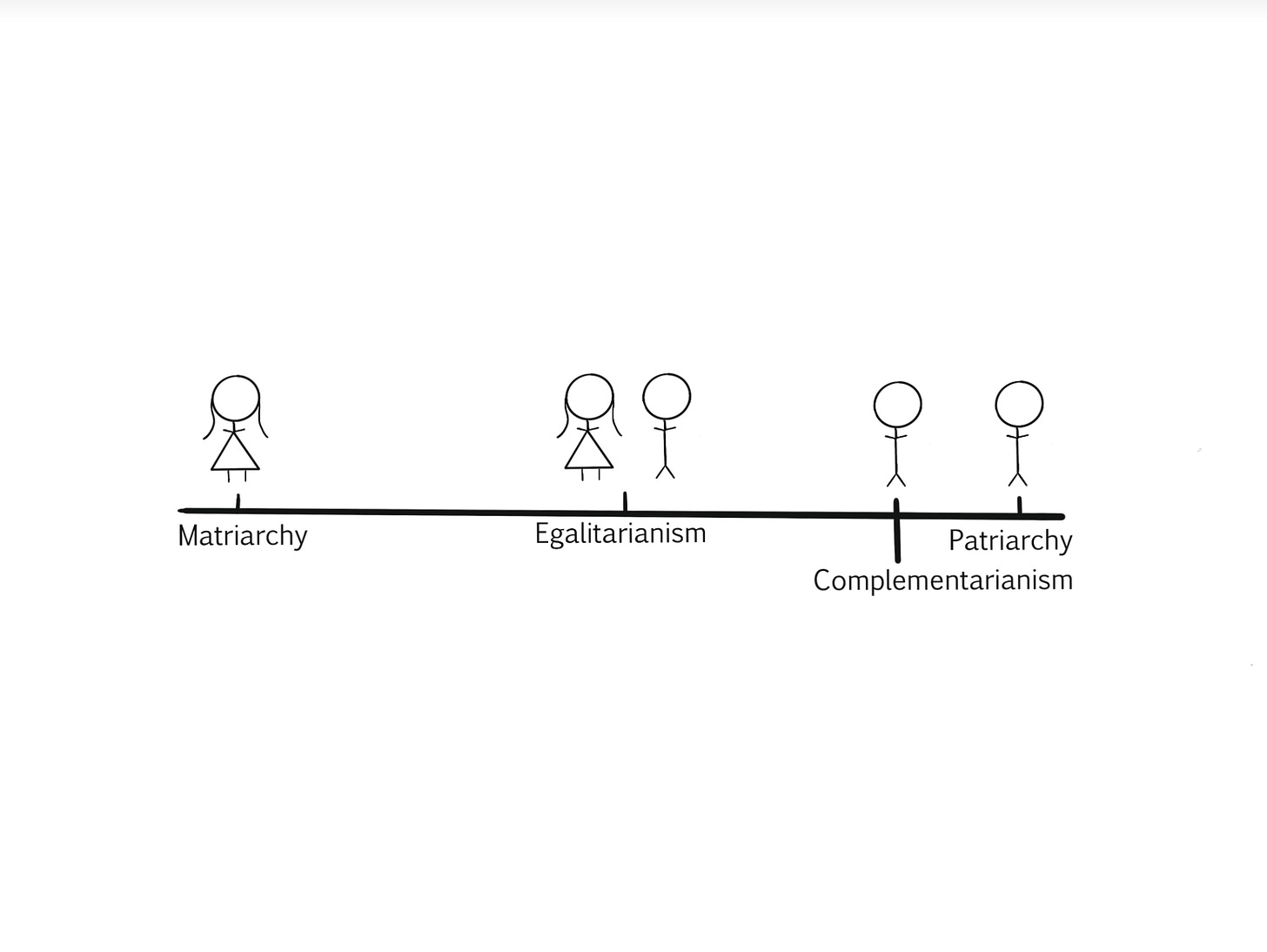

Debates continue whether complementarianism is patriarchy. Some complementarians themselves say, a resounding yes, and others say, no. I know many complementarians who would argue in essence women are equal, but in roles they are not. SO I made another sketch, more generous towards my complementarian brothers and sisters:

Even if you don’t see complementarianism as patriarchy, it remains under the umbrella and a close cousin. Restrictions, by nature bring about inequality. It’s hard to feel equal in essence when you are left to the men in charge to decide where, when and how you can use your gifts. That’s not equality.

It is confusing to be told you are equal as a female and yet unable to fulfill certain roles of leadership withing the church. How is there equality if there are signs on certain doors of the church that say, “no girls allowed”? However, matriarchy is not the answer either. All the egalitarians I know don’t want women to “rule everything” because that is not a picture of kingdom living either. Many of them know all too well the power dynamics of patriarchy, and do not want the opposite: matriarchy. They want equality.

When a complementarian pastor preaches on the definition of these terms but does so in a manner that reveals a hidden grasp for power, it breeds disunity within the church. It tells me that at the heart of it, his concern is for him to retain power. It’s the kingdom of Peter, concerned about his proximity to power. A desire for power is “not the concerns of God.” Jesus freely gave up his power, he gave it up to the “hands of the elders, the chief priests and the teachers of the law”[9] and he suffered and died because of that decision.

Egalitarianism, sometimes called mutuality, balances the scale so that no one gender is in power. By doing so it keeps the focus on the kingdom and brings equality to men and women alike. When we talk about theology, what if we used a Jesus focused, kingdom minded hermeneutic instead of a hermeneutic of power. What if we as church leaders ask, “Jesus where am I holding on to power? Where can I give it up? How can I multiply other’s gifts in the kingdom?”

Where have you held on to power this week? How can you empower others in the kingdom to life and walk in the fullness of their calling in Christ? Egalitarianism, or mutuality, is one way we can bring the kingdom of Jesus into our churches. It aims for a balance, equality for all through Jesus.

[1] Matthew 16:23 (NIV)

[3]https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20111128210940983#:~:text=Literally%2C%20a%20community%20of%20related,no%20doubt%20that%20matrilineal%20societies.

[4] https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100310604

[5] https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095743731.

[6] https://www.cbeinternational.org/resource/what-biblical-equality/

[7] https://cbmw.org/about/danvers-statement/

[8] https://cbmw.org/2020/08/10/why-i-am-a-complementarian/

[9] Matthew 16:21 (NIV)

It seems to me that Peter Lombard got it right a millennia ago: "she {Eve} was formed not from just any part of his (Adam's) body, but from his side, so that it should be shown that she was created for the partnership of love, lest, if perhaps she had been made from his head, she should be perceived as set over man in domination; or if from his feet, as if subject to him in servitude. Therefore, since she was made neither to dominate, nor to serve the man, but as his partner, she had to be produced neither from his head, nor from his feet, but from his side, so that he would know that she was to be placed beside himself

Reminds me of this from Orwell’s satirical novel, Animal Farm: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.” Words are important but actions show the true intent. Love your example of closed doors in the church—so true.