Invisible and Visible Institutions

African American Christianity

“Of all the striking aspects of antebellum Black Christianity, perhaps what is most amazing is that it developed at all. Christianity was the religion of the oppressors, who used it very consciously as a tool of oppression. Yet Black Americans found depths of hope and consolation in the faith that their white enslavers missed entirely. By the dawn of the twenty-first century, Black Americans remain the most religiously committed group in the United States, significantly more likely than any other group to attend church weekly, pray daily, and express absolute certainty that god exists.”

The story of the formation of Black Christianity forms into a turning point in the fifth chapter of Elesha Coffman’s Turning Points in American Church History: How Pivotal Events Shaped a Nation and a Faith (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2024).

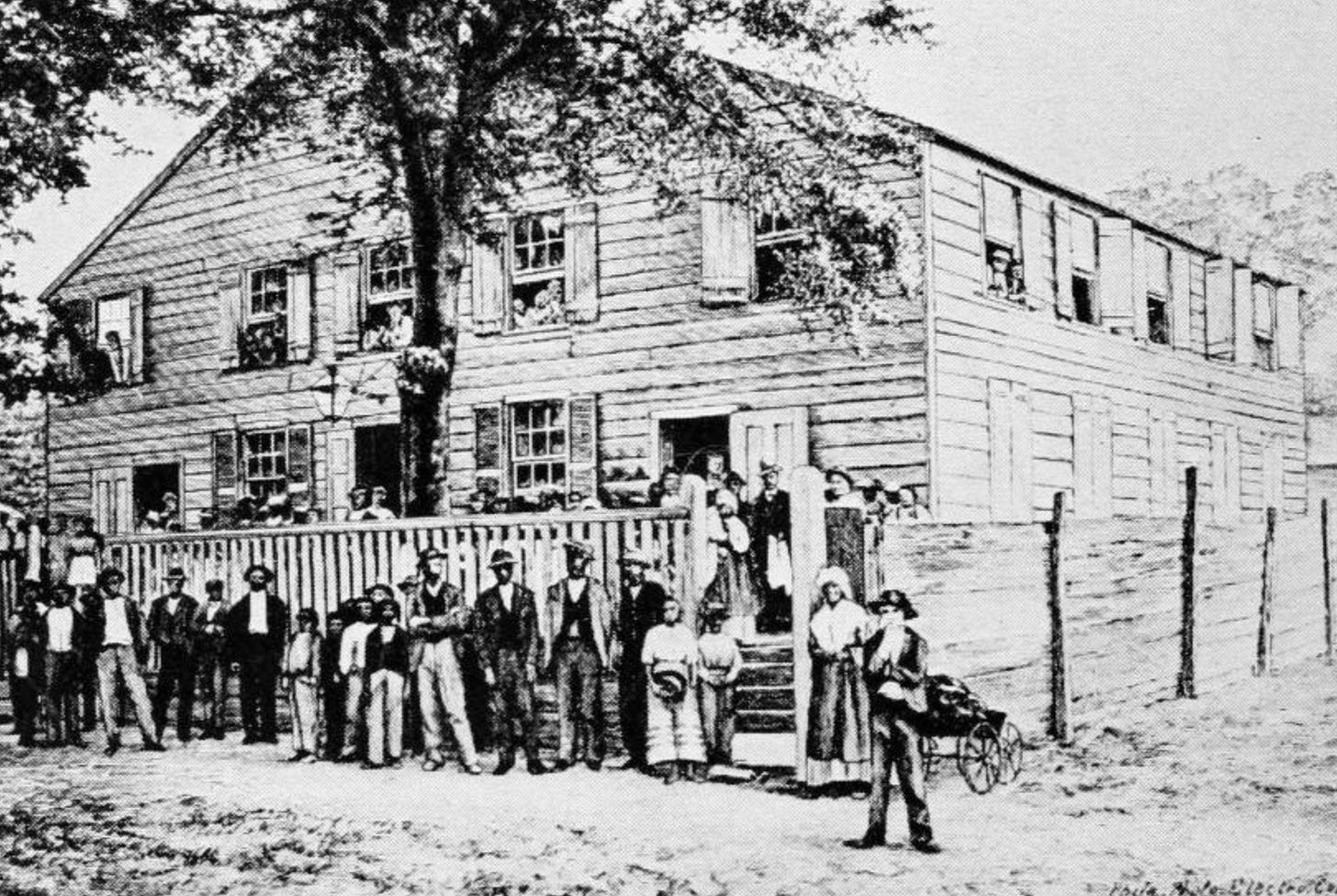

It has been customary, at least it has been for me, to think the earliest forms of African American Christianity occurred in the “invisible institution” of underground meetings, in the sundown to sunup gatherings, and not in official churches. Coffman sheds some light (for me) on this one. She takes us early to the first (official, visible) Baptist Church in Silver Bluff, Georgia, not far from Augusta. Along with the well-known poem by Phillis Wheatley in 1773 about George Whitefield, Silver Bluff becomes effectively a turning point in American history.

The land was owned by a white man named George Galphin; he wanted a more multi-racial society and church; he victimized both African American and Native American women; a man named Wait Palmer wanted to preach and evangelize Galphin’s society; many feared they would claim equality and freedom; Galphin permitted it. The first preacher there, as Coffman details it, was a Black preacher named George Liele. African American Christianity, then, cannot be assumed always to have begun with white preachers. In Galphin’s circle, then, collaboration occurred between whites and Blacks; David George, another Black preacher/pastor, eventually took over the “whole management” of the church. The Silver Bluff church today is in Augusta GA and is called Springfield Baptist Church.

The Revolutionary War created problems for the African American church as it was growing. In particular, of course, the British promised emancipation if they would join their side. Some of those who had supported the church work moved on to Canada, to Jamaica, and to Sierra Leone. Coffman pins the earliest missionary work onto to David George, but unless I’m mistaken, one could point to Rebecca Protten.

The Civil War set many Blacks free and it led to the “visible” institutions. The Black churches favored the Wesleyan side of the faith, which meant Anglican (Church of England), and that movement formed into the African Methodist Episcopal, under Richard Allen, and the African Methodist, under Absalom Jones, churches.

It’s too easy to get lost in facts and history. The essence of the Black churches was (1) the assumption of the white man’s faith, (2) the adaptation of the white man’s faith, and (3) the subversion of the white man’s faith by elements in the white man’s faith that were either suppressed or ignored. These three elements are very much part of the Black churches today, and it is why the Black churches don’t “fit” into the categories used by official narrative descriptions like “evangelical” or “Protestant.” When Exodus is the forming text, the faith shifts. Gender, too, played a different role – Coffman’s brief sketch of Jarena Lee is very helpful (more in Lisa Bowens’ wonderful book about Paul).

We hear more about the “invisible” church. Camp meetings gave rise to greater freedom, to the recognition of giftedness among Blacks, and to backwoods and secret meetings. This movement led to two major leaders. Nat Turner’s attempt at a violent revolution inspired by a vision about Jesus coming to judge, and Harriet Tubman’s non-violent, furtive leadership like “Moses” in the Underground Railroad. Over reactions and hangings and executions followed Turner; attempts to find Tubman failed and she was eventually honored even by the federal government. Freedom was never only spiritual for African Americans; nor is today. African American faith is holistic redemption.

Whites need to listen.

Would “holistic redemption” be about taking redemption out of the pews and out to families, neighbors, cultures of every kind, etc.?

And, what would be suggestions for further exploration of this for the white church to learn from?

Thank you, Scot keeping the fire going!

Thank you Scott