Repost (with slight edits)

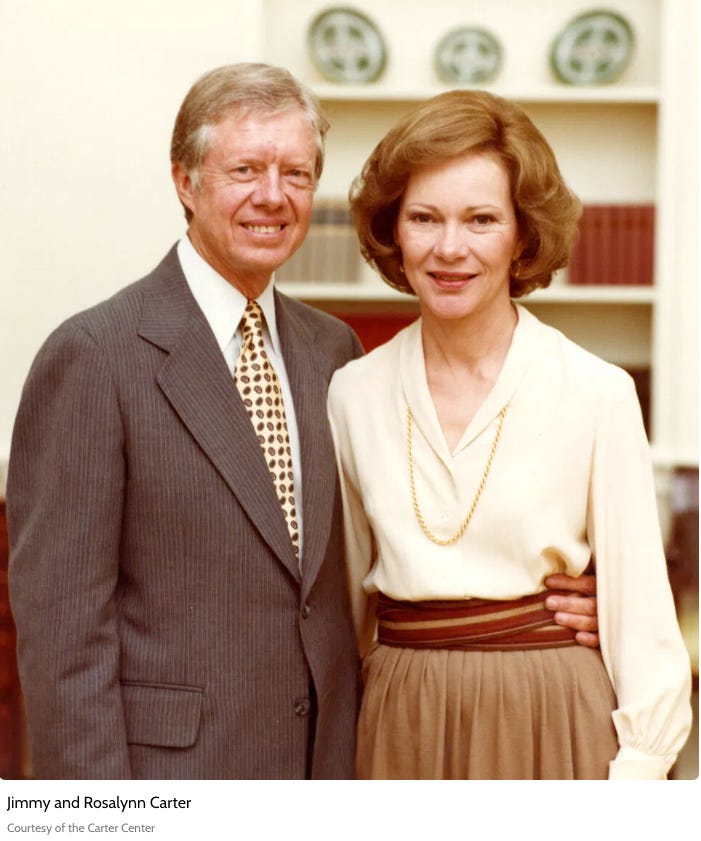

Jimmy Carter has passed away. One story here.

Mention former President Jimmy Carter and one is likely to get a response, and the most common is perhaps that Carter became more significant after his time at the White House that during his presidency. He is the only President in American history who used his presidency as a stepping stone to a more expansive career. Future historians may well demonstrate that Carter’s take on a number of issues — not least his routine questioning of our policies (one is tempted to write policings) and actions in the Middle East — was the wiser course. But what is perhaps most notable about President Carter is his (more or less) consistent application of his understanding of the Christian faith to public policy.

This post is based on the first edition of Balmer. Second edition here.

This is the theme of Randall Balmer, Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter (NY: Basic, 2014). Balmer combines a narrative of Carter’s life — from the obscure farms of southwest Georgia, to the US Naval Academy, back to Plains Georgia, the decision to get involved in politics, governor of Georgia and then the 39th President of the USA — with a study of how Carter’s faith shaped his public work. Following his presidency his advocacy of justice and peace and education, his defense of women’s rights, the Nobel Peace Prize, and his routine work in Habitat for Humanity. I limit myself to a few observations about Carter as presented in Balmer’s splendid new book, speckled as it is with fantastic vocabulary:

First, Carter’s faith is real and it has been a constant factor in his life. Yes, he had a conversion/rededication experience through his sister, Ruth Carter Stapleton, but from his early 40s on Jimmy Carter’s faith shaped his life substantively. Jimmy Carter’s “ministry” has been as a Sunday School teacher, both in Plains (where I think he still teaches in his 90s) and in Washington DC. Carter immediately saw trouble in the conservative takeover of the SBC and opposed many of its moves, not least its emphasis on the authority of pastors and its opposition to women in ministry. Carter believes firmly in the priesthood of all believers and that includes letting women do what God calls women to do.

Second, Balmer’s push is to see Carter’s own integration of faith and politics as progressive evangelicalism. He’s right at one level: Carter’s themes are the historic themes of American Christian progressives: from William Jennings Bryan on, including the Christian activism of such notables as Finney and Mark Hatfield. Carter was concerned with human rights, family, education, care for the poor, justice, natural resources, less imperialism, and peace-making negotiations in patience. The SBC was not part of the evangelical movement until the Reagan years and since then has been more than a substantive influence, so for me Carter’s progressivism mirrors the progressivism of the 19th Century and early 20th Century evangelicals more than the mid Century evangelicals we know today. I would call Carter a progressive (Southern) Baptist. One could of course contend the conservative evangelical movement since the 80s as a defection of the historic progressive impulse of evangelicals.

Third, which leads to an important theme in Balmer’s study, and one that deserves careful reading: Jimmy Carter was the favorite of American evangelicals in the election of 1976 but, owing to a variety of shifts and political moves on the part of evangelical activists, fell out of favor and, in effect, became a moderate or progressive Southern Baptist more than a progressive evangelical. Here’s the point: evangelicalism coagulated around conservative political platform — at the lead of Paul Weyrich and Jerry Falwell — in the late 1970s that led to the evangelical support of Ronald Reagan and the vilification (and worse) of Carter and his faith. What some of these leaders said about Carter’s faith was disgraceful and purposefully deceitful. Carter’s progressive Christian postures had a noble evangelical heritage. The conservatives wiped much of the evangelical progressive platform off the docket.

Fourth, Balmer details in this book a theme I’ve read in a number of his works that needs a constant reminder for those who’d like to revise the history. It’s simple: abortion did not precipitate the Moral Majority and the conservative evangelical platform. Segregation/integration in Christian school education did. The IRS in the early 70s began to apply pressure on Bob Jones University for its discriminatory policies and that governmental action led to a gradual but powerful congealing of forces around — mark this down — not the right to segregate but the invasion of religious freedom. That is, conservative evangelicals defended the right of a Christian school to establish its own beliefs and policies and the government had no right to pry into a religious school’s ways. I distinctly remember this debate creating concerns among evangelicals. It was not until about 1978 that abortion became the rallying cry of the pro-Republican evangelicals. So it was not Roe v. Wade but Green v. Connally that galvanzied evangelicals. Yes, to be sure, opposition to abortion then became a central platform, which Reagan endorsed (and then did barely a thing about it and this theme is also found in Balmer’s book and raises the specter that the conservative evangelical caucus was more or less used).

Fifth, the conservative evangelical activist impulse was a juggernaut that removed Carter from office and established what James Davison Hunter called the culture wars.

But this must be said: No other president has been more of a public servant than Jimmy Carter.

Redeemer was an excellent book.

Thank you . Former President Carter was the first president when I was at the age able to vote