More Than This

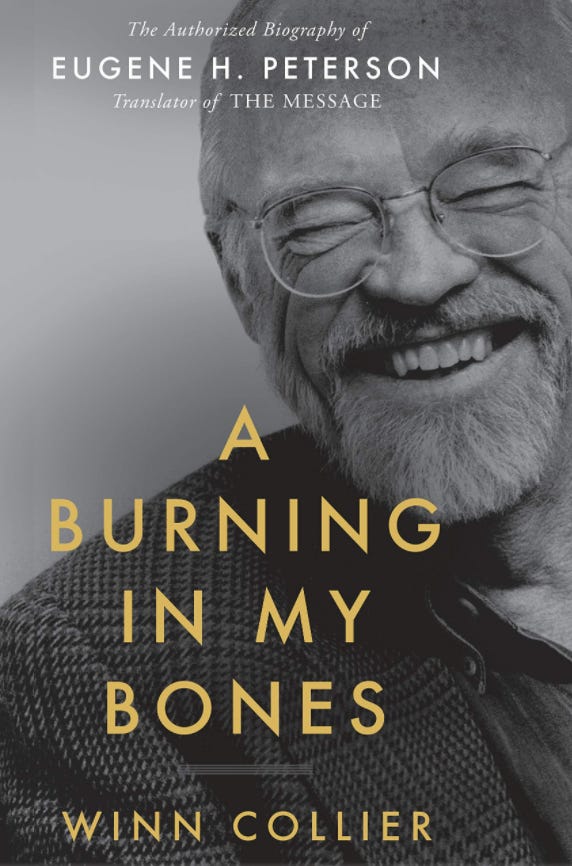

A noticeable theme in Winn Collier’s biography of Eugene Peterson called A Burning in My Bones (pp. 148-168; for the reading plan) is a drive, a push, an aching, a burning, a quest that life and pastoring and his vocation were more than what he was doing.

Many experience this desire for something more in various periods of life and some seem to experience it most of life. Some not at all. Over Peterson’s Assemblies of God, his college experience, his seminary education, his learning what pastoring was, and perhaps most especially, pastoring itself was a lingering ache that “Yes, this is what I’m to be doing” but there’s something more that alone can get to the heart of what I’m best equipped to do.

How about you?

Have you experienced such, a kind of “life and my calling has got to be more than this”?

How do you get through such an experience?

Let’s call it liminality. Life in between what it was/is and what it should be.

Some people land on a calling early and never move. Others wander into one and realize, years later, well that’s how my calling came about. And others move one step at a time into a calling and sense at times there will be something more.

“Like most profound inner transitions, Eugene’s growth into his vocation happened slowly, by means of human encounter and time spent in prayer and the long obedience of pastoral work, not through mighty revelations or rational argumentation” (148).

Collier’s honest about Peterson in so many ways: his ache for the more occurred in the midst of a full and (overly) busy life. His daughter Karen once said at dinner that he had been gone 27 evenings in a row. At the elders meeting it all came to a boiling head: he quit. They said what do you want?

What comes next has been the undoing or the depression point of many pastors. What comes next, in fact, would change pastors, churches, and seminaries. What comes next is a different kind of pastor, which is at the heart of his “more than this.”

Peterson:

I want to be a pastor who prays. I want to be reflective and responsive and relaxed in the presence of God so that I can be reflective and responsive and relaxed in your presence… I want to be a pastor who prays and studies…. I want to be a pastor who has the time to be with you in leisurely, unhurried conversations so that I can understand and be a companion with you as you grow in Christ … I want to be a pastor who leads you in worship… I want to have the time to read a story to Karen… I want to be an unbusy pastor (149-150).

Their response: “What’s stopping you?”!!!

They changed their structure and their meeting schedules and Peterson was set loose for a “more than this” kind of pastorate that forms the vision of many today. (Not enough.)

He began to dress casually in all but the official church services.

Instead of credentials and diplomas, on his wall were pictures of three people: Alexander Whyte, John Henry Newman, and Baron Friedrich von Hügel.

His relationship with his father was distant, with his mother it was close, and he was conscious of needing to be a better father so he spent more time with his children – and Collier gives poignant illustrations for each. But…

The church was good work, holy work, but Eugene didn’t always draw the boundaries he should have. He at times was more available to his parishioners than to his family. Years later he would recognize – and regret – these failings. But it was hard for Eugene to see it clearly at the time (159).

Peterson had two callings: to pastor and to write. The former prompted the latter but it was not until he could become a writer than he the “more than this” was resolved.

For writing his favorite was Dostoevsky.

He was not an early success and got many rejection letters.

Five Smooth Stones for Pastoral Work did not do well. His next book, A Long Obedience in the Same Direction, illustrates what many have experienced writing. He had a hard time getting anyone to take manuscript. 23 submissions, 23 rejections. Jim Hoover at IVP, though not impressed with the early parts, was hooked and IVP published it. Jim had to cut his overused of adverbs.

The rest is history.

The “more than this” was over. I sneak here into the next chp to work on this theme a bit more.

… people around the country were picking up books with his name on them-picking them up and sensing they’d found a voice that spoke their true language. Vast numbers of readers recognized in Eugene’s words a hunger they’d forgot-ten, a craving for an authentic encounter with God. They were hungry for a vision calling them into the wondrous expanse of a life that honored what it meant to be a beloved (though finite) human living under the mercy of a magnificent, generous, infinite God. They found all this in the words of a pastor from Maryland, and they couldn’t get enough (175)

His more and their more were the same.

In part.

I am again at the place of feeling the lack of fit between all the stuff inside me-vocational/spiritual energies-and the work I do here as pastor of Christ Our King. The critical question: is the “lack of fit” because I am out-of-proportion, my life is losing a base in humility -- in letting go? Or is it because there is something else or more that God is wanting me to do (180)

I end there because “more” is a human longing for what God alone in God’s eternity can fully quench.

Eugene’s ‘more’ was, for me, at the heart of his insightful book on Jonah. After ‘working the angles’ that Peterson said no pastor can be without, Tarshish (by Eugene’s definition) still called - the want to be somebody, to make a splash, to be successful (with dangerous nuances) and gain notoriety, and that, over against the certain failure and obscurity of ministry in Nineveh! ‘Church Growth’ was the siren call of Tarshish in one of my ‘more’ episodes. Volumes on ‘how to be a successful church grower’ were piling up on my study floor. In another, smaller stack was Lewis, Brueggemann, Calvin Miller, W. Willimon, B. Manning, G. Fee and, yes, Peterson’s quiet voice saying ‘more’ may be so simple that you look past it. Liminality, in that season, was 6 years in a tiny, remote oilfield community in NM. It was prayer, study, slow conversation, practicing sermons on cows pastured nearby, reading deeply, helping people find the sacred in pump jack maintenance, in gas line calculations and finding beauty in barren sand hills. Circumstances, prophets, Jesus and mentors from my smaller pile of books helped me find more in less, success in simplicity, fullness over frantic busyness and, as mentioned in your comments Scot, that God alone could satisfy my own ache for more. I’ve not arrived in any sense where the ‘more’ has completely been answered (similar to my building/construction skills, I find myself a Jack of all trades, master of none sort of person), but when in the struggle it’s always to ones like Eugene that I find myself in conversation, again. Enjoyed this piece of Eugene’s journey immensely!! Thank you! peace

I really appreciated this part of the book and it resonates with me. I headed off to Moody in 1981 because I felt a lifelong call to be a pastor. I had ignored it for years planning instead to be a sportswriter instead. In my last year at Moody I had a pastoral counseling class and a part of me thought, "this is what I really want to do, this and preaching, but not all the other stuff that goes along with being a pastor." But I was pretty sure I was going to be the next big thing, perhaps the next Chuck Swindoll and I didn't want to limit God by being a counselor. I worked as an assistant pastor at my home church for the next 5 years, and although I loved parts of it, there was so much that didn't go well. The next 8 years were a wilderness and the feeling of wanting to be a pastor never left me, but the idea began to come to me that, in a way, I could "pastor" people by being a counselor. I headed off to CCU in 1997 to study under Larry Crabb, whose teaching my pastoral counseling professor had highlighted many years before, and whose books had come to mean a lot to me. I've now been a counselor in private practice for 22 years and I love it, but the feeling of being a spiritual director/pastor of sorts has never left me. Reading this about Peterson and how his particular work began to be more and more clarified for him was so helpful to me.