That Time

One cannot emphasize enough the significance of time in biblical studies. In particular, in how Jesus, Paul, Peter, et al, think of what happened in Jesus. In more particular, in conceiving of the Christ event as fulfillment of Israel’s story or the Messianic Age of Israel’s story, as the inauguration of the kingdom, as the launching of the Age to Come or the New Age.

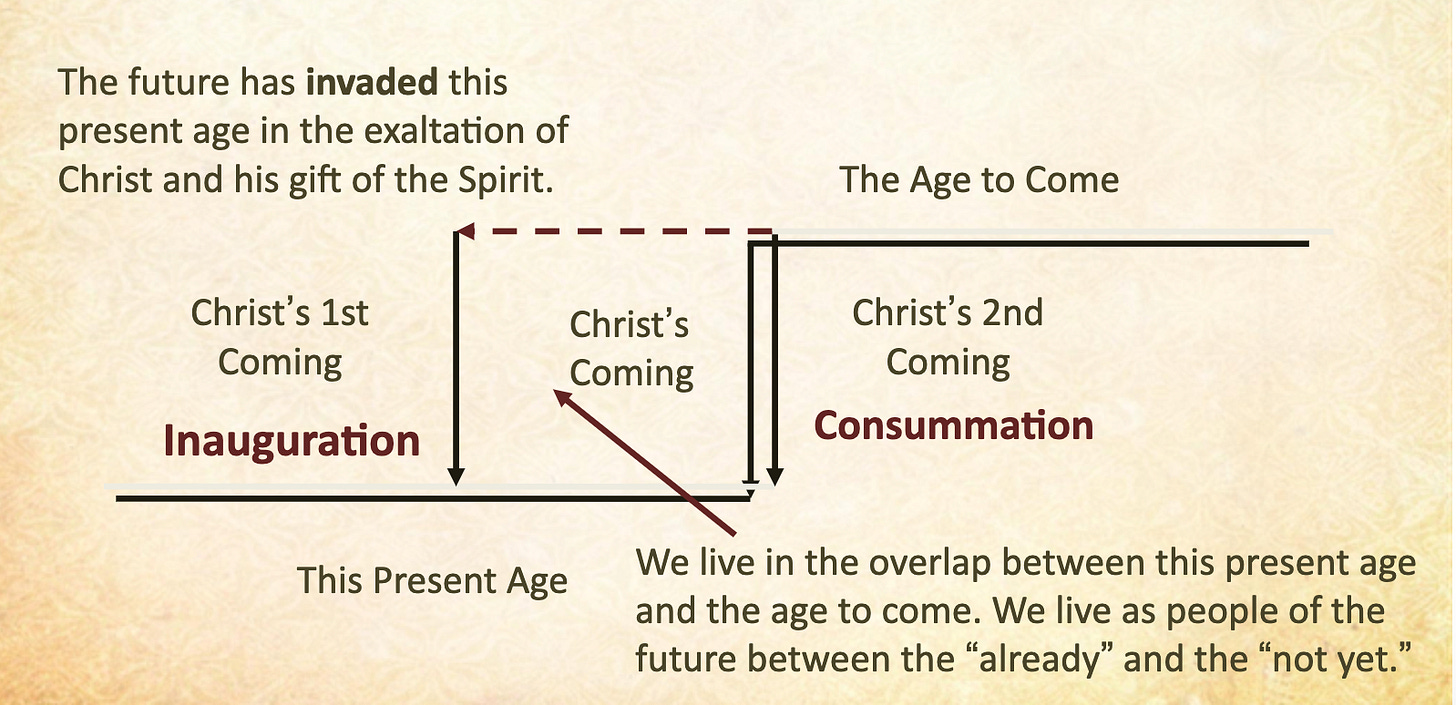

The result of this for believers in Jesus is that they live in between the times or in the overlap of the ages. I Googled inaugurated eschatology and saw dozens of graphs, all of which I think go back to George Eldon Ladd’s A New Testament Theology. Inaugurated eschatology, however, was not the brainchild of Ladd, even if many in the evangelical fold picked it up from him. I read it, subsequent to my reading of Ladd when his theology was published, in Georg Kümmel and in Oscar Cullmann, from whom it can be inferred Ladd learned some or more of what he presented. Here’s a graph of the basics.

Source: https://slideplayer.com/slide/6817164/

While some have argued Jesus, Paul, Peter, and James – at least – expected the Age to Come to arrive in their lifetime, others have ignored that discussion and simply used a larger schematic to frame time in the NT. Some are salvation-historical (or redemptive history) and others are apocalyptic in their approaches. The former sees time as linear and sequential and teleological while the latter frames time more in terms of God’s Eternity irrupted in time. Some want to wipe out salvation history with apocalyptic; others think they work together well.

But time as real (objective) and linear and sequential (past, present, future) and teleological (future kingdom of God) is the bedrock of how NT and systematic theologians frame the eschatology and concepts of time. To disrupt that linear, sequential, teleological sense of time disrupts everything. At least it would scatter the cards on the table dramatically.

L. Ann Jervis does just that in her new book, Paul and Time: Life in the Temporarity of Christ. John Barclay says this about Jervis’s book:

Jervis's central thesis is that Paul understands the Christ event not as the inauguration of a new time (a “new age”) or as the intrusion of timelessness (“eternity”) into the world of time but as the enclosure of one kind of time (death-time, or time determined by decay) with within another kind of time (life-time, or the life of Christ).

Critical here is that she does not think of time as periods of time. And, Barclay records his summary of how she envisions of the Christian life in this new framing of time:

Equally importantly, union with Christ is not partial or incomplete, as if the believer lives a bifurcated life, partly in the realm of death and partly in the realm of life. On Jervis's reading of Paul, the believer lives completely and exclusively in the life of Christ.

So much from Barclay’s helpful introduction.

Jervis knows she’s proposing something significant that counters our instincts. “What I have found most challenging is the idea that those in Christ are exclusively in Christ.” If in Christ, Christ-time pertains to those in union with Christ. Those not in the life-time of Christ are in death-time, “which is in reality non-time.” “God’s temporality,” in other words, is the only “real time.” Thus, “Being joined to Christ is to live in a temporality entirely distinct from that of the present evil age.”

She has a nice section on the history of thinking about time in theology. Most are Newtonian, that is, they think of time in linear, sequential, teleological ways. She has plenty on Augustine who pondered time, timelessness, and eternity in his Confessions. I will avoid some of Augustine’s ideas about time that she presents. He was a linear time guy and thought it best squared with the Bible. Eternity has been conceived, in the simplest of categories, as either timelessness or the intensification of all time in God’s time, or also as endlessness or infinite duration, and also as the unity of all time (Pannenberg).

At issue here is a big question she has pondered: Have we framed Paul in the terms of how we – in the modern, postmodern world – conceive of time so that we have imposed our theory and theology of time on Paul?

That’s the context for Jervis’s study, and I hope you join us on this Substack as we continue to discuss her way of understanding Paul’s view of time.

Thank you Scott

Oh no! Now I need to read another book. Don't you know I don't have time for that? LOL

Seriously though, this sounds intriguing. I will definitely pick up a copy.